The Growing Problem of Older Adult Homelessness

While the number of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness has decreased over the last ten years, the number of older adults experiencing sheltered homelessness is on the rise, as we report in Housing America’s Older Adults 2019. Incomes for the lowest-income older adults have not risen as fast as rents, leaving a growing number of older adult renters at risk for homelessness as they struggle to cover their housing costs.

Older adult renters are a large and growing group. According to our 2018 Household Projections, the number of renter households headed by someone age 50 and over is expected to grow from 16.0 million in 2018 (35 percent of all renters) to 21.2 million in 2038 (40 percent).

These older adults are entering retirement in worse financial shape than same-age households in 2001. While many older adult homeowners have built up savings and wealth, our tabulations from the Survey of Consumer Finances show that renters aged 50–64 had a median net wealth of $4,990 in 2016, down in real terms from $8,860 in 2001. The drop was less steep for renters age 65 and older, decreasing from $8,810 in 2001 to $6,710 in 2016. Renters in the bottom income quartile for all households had a net wealth of only $1,900 for 50–64-year-olds and $1,100 for those age 65 and older, leaving little buffer for weathering financial shocks.

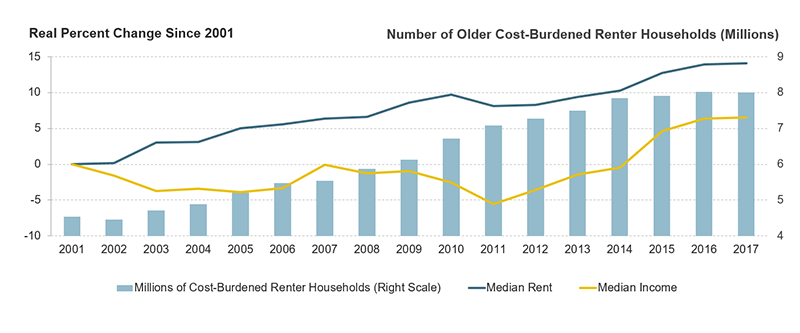

The decreasing wealth of older renters is related to the erosion of household incomes as rent increases outpaced income gains over the last 15 years (Figure 1). From 2001 to 2017, the median monthly incomes of renters age 50 and over increased 6.6 percent, up from $2,310 to $2,460. However, median rents over this period rose 14 percent from $790 to $900. The increase in rents relative to incomes has pushed up the number and share of cost-burdened older adult renters spending at least 30 percent of income on housing costs. In 2001, 4.5 million renters age 50 and older were cost burdened, amounting to 45 percent of all older adult renters. That number rose to a new high of 8.0 million in 2017 (50 percent).

Figure 1: The Number of Cost-Burdened Older Adult Renters Hit a New High in 2017 as Rents Outpaced Incomes

Note: Older adults are age 50 and older. Incomes and rents are adjusted to 2017 dollars using CPI-U All Items. Rents include utilities. Cost-burdened households pay more than 30% of income for housing. Households with zero or negative income are assumed to have burdens, while households paying no cash rent are assumed to be without burdens.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

High housing costs have large consequences for older adults’ household budgets. After paying rent, the lowest-income renters (defined as those with incomes in the bottom quartile of all households) aged 50–64 had only $560 each month to cover all other expenses. Renters 65 and older had even less at $495. With little income left over after paying rent, older adults may have to make cutbacks on other expenses. Our analysis of the Consumer Expenditure Survey shows that the cost-burdened renters age 65 and over who were in the lowest expenditure quartile (a rough proxy for income) spent less on food, healthcare, and transportation than their unburdened counterparts.

With so little cushion, a financial shock, such as a costly health episode or an unexpected rent increase, could leave older adults unable to pay their rent. Eleven percent of older adult renters who moved in the last two years were forced to move; the vast majority reported that a landlord, bank, or government entity evicted them. These forced moves can result in people doubling up, living in less suitable or preferable housing, or even becoming homeless.

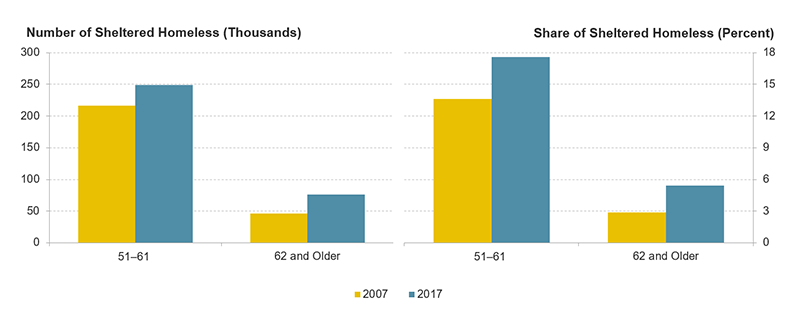

Indeed, the number of older adults experiencing sheltered homelessness is growing despite declining sheltered homelessness among younger age groups. According to tabulations from HUD’s Annual Homeless Assessment Report, the number of sheltered homeless aged 51–61 increased from about 216,000 in 2007 to 249,000 in 2017 (Figure 2). The number of sheltered homeless also rose for those 62 and older, from 46,000 to 76,500. Older adults now make up 23 percent of the sheltered homeless population, up from 16.5 percent in 2007.

Figure 2: Sheltered Homelessness is Increasing Among Older Adults

Source: JCHS tabulations of 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report: Part 2.

Based on the income and wealth trends for the lowest-income older adults, the outlook for homelessness is bleak. A study conducted at the University of Pennsylvania found that adults born 1955–1965 (currently aged 54–64) have had higher rates of homelessness throughout their adult lives and are likely to add to the number of homeless older adults as they age. The study estimates that in New York City, for example, the number of homeless older adults age 65 and over will increase from its current level of 2,600 to 6,900 by 2030. Older adults experiencing chronic homelessness may also have difficulty living independently because homelessness accelerates the aging process and worsens health.

Without meaningful action now, the homelessness crisis for older adults will only worsen in coming years. Investments in affordable housing and income supports for vulnerable older adults are needed to help these households from falling into homelessness. Permanent supportive housing with services will also be crucial for addressing the needs of older adults currently experiencing chronic homelessness.