Racial Stratification and Suburban School Segregation

The draw of white and well-resourced suburban public schools has long fueled segregation in America’s metropolitan areas, but what happens when these schools become more diverse, as they have in recent decades? In a new working paper based on a unique dataset from Los Angeles County, I find that nearly 40 percent of suburban white and Asian children are sent to non-assigned schools, whether public or private, and this rate is considerably higher in suburban communities with larger shares of Latino and Black children.

These findings challenge the long-held perception that access to advantaged local public schools is both a key feature of suburban life and a key reason why white families have left the core-city for the suburbs in droves since the mid-20th century. In fact, suburban schools are not what they used to be. High rates of suburbanization among minorities and immigrants have transformed many American suburbs and their schools from lily-white enclaves to multiracial milieus. By the mid-2000s, the white share of students in suburban schools nationally was below 60 percent and in Sun Belt suburbs the percentage was even lower.

A large body of research has examined contemporary school enrollment patterns in core-city school districts like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. In these places, school-choice policies have upended the traditional residence-based system by which children were historically assigned to public schools. Magnet and charter schools have rapidly expanded, private school vouchers have increased, and school enrollment restrictions have loosened. Although these shifts were purportedly intended to facilitate inner-city minority students’ exit from under-resourced and underperforming schools, research suggests it is white and Asian families in core cities who disproportionately enroll in magnet, charter, or private schools – especially when residing within neighborhoods containing large concentrations of Black and Latino children.

Whether similar minority avoidance patterns of school enrollment occur in suburban communities remains unknown. Expectations are unclear for two reasons. First, compared to cities, private, magnet, and charter schools are in much shorter supply in the suburbs. Second, suburban families may hesitate to forsake the idealized vision of a neighborhood-public school “package deal” that likely contributed to their decision to live in a suburban locale.

Against this backdrop, I set out to examine whether suburban white and Asian parents still value racially homogenous schools, and if so, how they enact these preferences in racially diverse suburbs. Do suburban white and Asian families exhibit stronger race-based preferences than core-city white and Asian families? Are they willing to send their children far distances to non-assigned, whiter schools?

To examine these possibilities, I used school enrollment and residential location data for over 2,000 children ages 5–17 during the 2000s from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey, linked to educational administrative data. The survey tracks families across all of Los Angeles County. About half of the surveyed families reside in places where public schools are run by the core-city district of Los Angeles Unified School District – which spans the city of Los Angeles, over 30 other municipalities, and several unincorporated regions. But the other half live in areas served by separate suburban school districts, such as the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District and the Pasadena Unified School District.

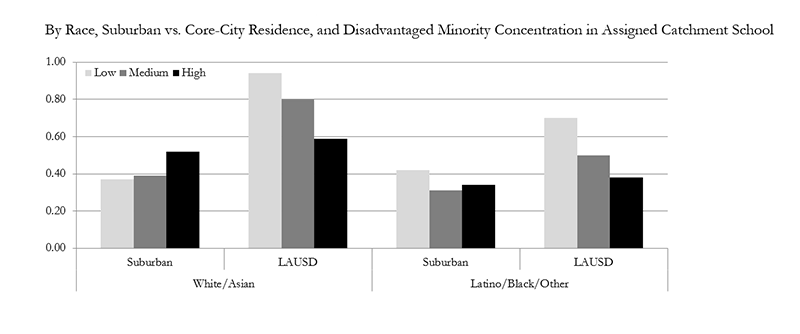

Figure 1. Proportion of L.A.FANS Children Enrolled in Any Type of Non-Catchment School

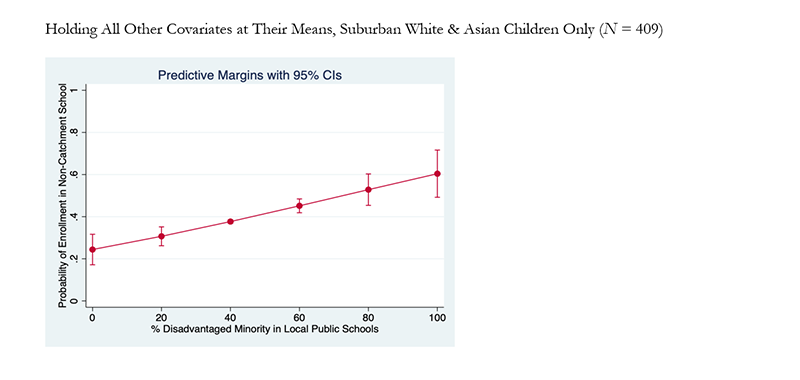

I found that 40 percent of suburban white and Asian families within Los Angeles County exercised some form of school choice during the 2000s and that they were particularly likely to do so if the children’s assigned school had higher concentrations of Latino and Black students. Specifically, I estimate that a 20 percentage point increase in the disadvantaged minority composition of white or Asian families’ local public school increases the probability they will opt out of that school by 10 percentage points. Perhaps more surprisingly, suburban white and Asian children’ school decisions appear more sensitive to local public school racial composition than do those of their similarly-situated core-city counterparts.

Figure 2. Estimated Effect of Percent Latino or Black in Catchment School on Non-Catchment School Enrollment

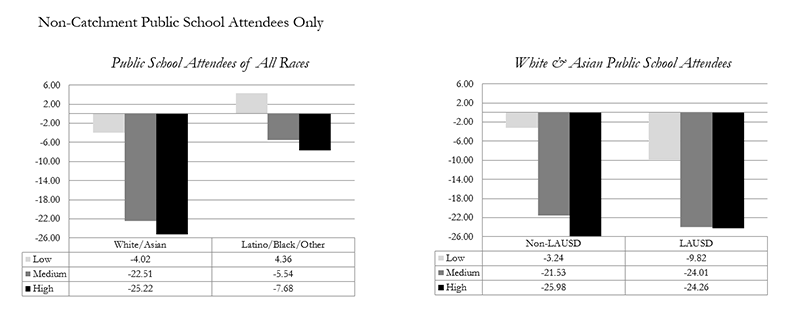

The strength of race-based preferences among white and Asian suburbanites is made tangible by two key statistics. First, white and Asian suburban children attending a non-assigned school were sent to campuses very far from home: about ten miles, on average. Second, suburban white and Asian families who opted out of assigned schools containing over 50 percent Latino/Black students attended schools that were nearly 25 percentage points lower in Latino/Black composition.

Figure 3. Mean Difference in Percentage of Students who are Latino or Black Between Enrolled Public School vs. Assigned Catchment School

Strikingly, these same families often sacrificed school quality in the process. Their selected schools rank 2.5 deciles lower in academic quality, on average, compared to their assigned schools. Racial composition, not academic quality, appears more central to these families’ school enrollment decisions.

Overall, the findings suggest that neighborhood and school researchers should expand their focus beyond the two traditionally-emphasized pathways of segregation: (1) residential flows from diverse urban to homogenous suburban communities, and (2) educational flows of advantaged core-city dwellers from traditional public schools to magnet, charter, and private schools. My study reveals a third path, one in which diverse suburbs and sparse non-traditional school options spur white and Asian families to send their children long distances to whiter but often poorer-performing public schools.

These racial preferences appear so entrenched that simply reducing the availability of charter, magnet, or, private schools or publicizing non-demographic school quality measures are unlikely to stymie educational segregation. Until racial preferences attenuate, policymakers might need to take bolder – and admittedly, more politically controversial – actions such as restricting advantaged families from activating school choice unless their assigned schools are truly failing.