Fertility Rates and Age Structures – The Underpinnings of Replacement Fertility in the U.S.

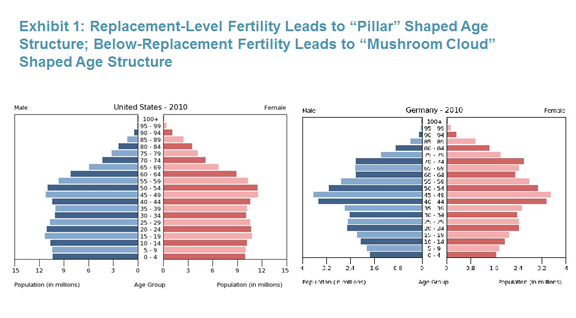

The U.S. fertility rate is at near replacement level, where a woman bears two children over her lifetime (just enough to ‘replace’ herself and her partner). The Total Fertility Rate (TFR), which is how many children the average woman in the U.S. will have if she survives through the reproductive ages and bears children at each age at rates U.S. women are currently experiencing, is just below this level. Replacement fertility leads to a “pillar” like age structure, where the base of the pillar (children) contains about the same number of people per five-year age group as the middle of the pillar (parents). For the U.S., that number is currently about 20 million (Exhibit 1).

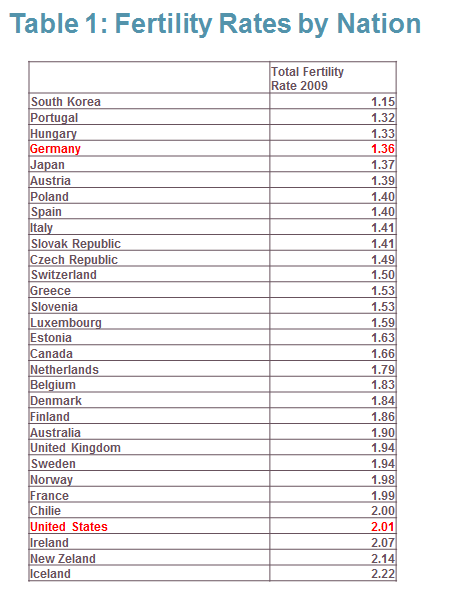

This situation can be contrasted with fertility rates and age structures in most other industrialized countries. Below-replacement fertility in much of Europe and in a number of Asian countries has created “mushroom cloud” shaped age structures where the numbers of children are just fractions of the size of the parents’ generations. In Germany, for example, the 0-4 and 5-9 age groups are only about half the size of the 40-44 and 45-49 age groups (Exhibit 1). Age structures for other countries with TFRs of 1.6 or less are broadly similar to Germany’s (Table 1). Such an imbalance in age structures has the potential to create enormous problems for these societies in areas such as institutional stability (e.g. schools), labor force succession, housing market dynamics, and old-age social security. Shrinking class sizes, workforce shortages, declining demand for larger homes that prevent older households from downsizing, and payroll tax collections that are insufficient to pay for retirement benefits are all consequences of long periods of below-replacement fertility.

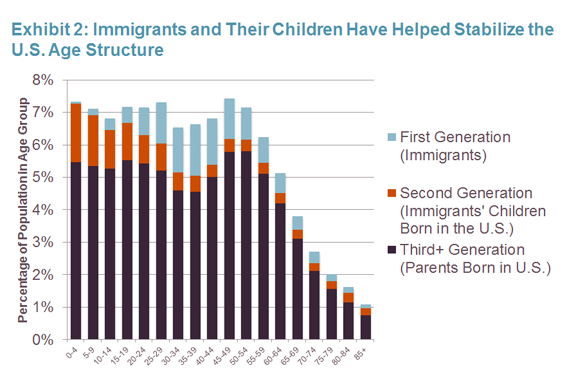

So why is the U.S. such an outlier compared to other industrialized countries in having experienced recent near replacement-level fertility and a relatively healthy age structure? And, is the U.S. likely to retain this advantage in the future? The answers to these questions point to the importance of immigration in shaping the present demography of the U.S., and to uncertainty about future levels of immigration and the role it will play in the future.

Decomposing the U.S. age structure into immigrants (first generation), the children of immigrants born in the U.S. (second generation), and third or higher generations (parents born in the U.S.), illustrates the importance of immigration in both backfilling the smaller baby bust cohorts born between the mid-1960s and mid-1980s and in increasing the cohort size of children born here in the past 20 years (Exhibit 2). According to a recent Pew Research Center report, immigrant fertility rates are about 50 percent higher than native-born rates. While in 2010, only 17 percent of women of reproductive age were immigrants, immigrant women bore a quarter of all children born in the 2000s. Replacement level fertility in the 2000s was achieved by above-replacement immigrant fertility counter balancing below-replacement native fertility.

The future stability of the age structure of the U.S. will depend on levels of immigration and on fertility trends of both the native born and of immigrants. The Pew report cited above documents how dramatically fertility rates have fallen since the Great Recession, with the largest percentage declines occurring among immigrants. Between 2007 and 2010 the number of births per 1,000 women age 15-44 (the General Fertility Rate) fell for native-born women by 6 percent while for foreign-born women the decline was 14 percent. Whether fertility declines have been mostly driven by high unemployment and low wages and so will rebound with an improving economy is too soon to tell. Any rebound could still leave fertility levels below the replacement rate. But in any case, it is unlikely that U.S. women will soon adopt the very low levels of childbearing that characterize much of the developed world. The influence on fertility of “pro-family” fundamentalist religions in the U.S. and the not-unrelated political hostility to birth control and abortion in many parts of the country continue to support higher levels of U.S. childbearing.

However, the size and composition of future streams of immigration are very much in question. Immigration reform has been slow to gain traction in the U.S. Congress, and the outcome of any new legislation on future immigration levels remains uncertain. More to the point, perhaps, is the fact that several important sending countries are undergoing fundamental transformations in both their economies and demographics that will diminish their propensities to send immigrants. For example, Mexico accounts for about 30 percent of all foreign-born living in the U.S., and immigration from Mexico has long been a safety valve to release excess population growth in that country. But Mexico has reduced its fertility by over one-half since 1985, with much of the reduction occurring in the past decade. In the future, as long as Mexico’s economy continues to prosper, we can expect fewer will need to leave Mexico to find work. Similar transformations are occurring in other sending countries such as India and China. Age structures in these countries have begun to transform from “pyramid” to “pillar” shapes.

Before closing, I want to say a few words about one industrialized country, Sweden, which has succeeded in maintaining near replacement fertility without depending on high fertility immigrants. There are indeed immigrants to Sweden who are needed to fill certain jobs, but they mostly come from other low fertility countries in Europe, especially the Balkans, and the immigrants retain the low fertility of their countries of origin. Sweden has a long history of low native-born fertility going back to the 1970s, and has gradually adopted strong social policies to encourage its citizens to voluntarily become parents, including generous maternity/paternity leaves, significant health care and housing benefits, and low-cost, high quality, and readily available daycare. But even with such strong pro-natalist policies, Sweden can barely keep its fertility at near-replacement levels.

We should be thankful that our recent history of high-fertility immigration has helped create an age structure that will lead to far fewer problems in the near future compared to those facing other industrialized countries. Whether we continue to retain this advantage will depend on future levels of both immigration and fertility (of both the native-born and the newly arrived). To avoid the U.S. moving toward a mushroom cloud like age structure, absent widespread pro-natalist programs and policies as in the case of Sweden, the depressed immigration levels and declining fertility trends of recent years will need to be reversed.