Digging Deeper into the Story: The Widespread Implications of the Growth in High Income Renters on Low- and Middle-Income Renter Households

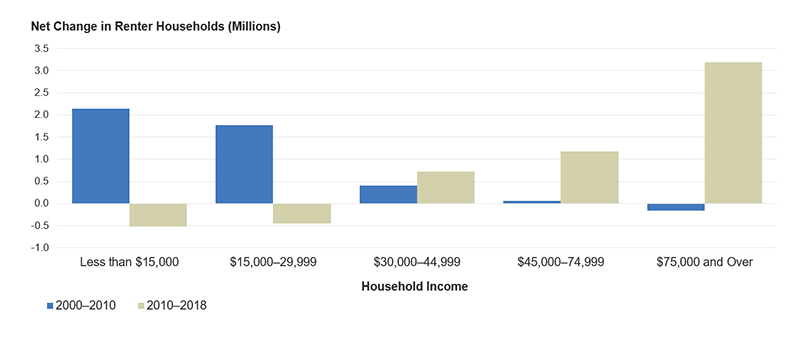

One of the major stories highlighted in our new America’s Rental Housing report is the growth in high-income renter households. After not growing between 1990 and 2004, the number of renter households shot up by over 10 million households since 2004. In the early years, between 2004 and 2010, households earning less than $30,000 per year accounted for two-thirds of the growth in renter households. But between 2010 and 2018, more than three quarters of all growth was among renters with incomes of $75,000 or more (Figure 1).

Figure 1: High-Income Households Have Driven Most of the Growth in Renters Since 2010

Note: Incomes are adjusted for inflation using the CPI-U for All Items.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

Meanwhile, rental markets are tight, with the US vacancy rate at its lowest level since the mid-1980s. The combination of high-end-driven rental growth and tight markets has created a challenging dynamic with several implications for renters and rental markets that practitioners, policy makers, advocates, and analysts need to keep in mind. These implications include the following:

Growing demand from high-income renters puts pressure on middle- and lower-income renters.

High-income renters don’t just rent high-end units. Some high-income renters choose to rent units that would be affordable to renters with lower incomes, thereby reducing the number of affordable units available to lower income households.

Even if they wanted to, though, high-income renters couldn’t all rent high-end units because there are far more high-income renters than high-end rental units. Thanks to the work of the National Low Income Housing Coalition and the Urban Institute, the lack of low-end units affordable to low-income renters is well known, with only 37 units affordable and available for every 100 extremely low-income renter households nationwide. But as we noted in 2018, there is also a wide gap between the number of high-income renters and high-end rental units.

High-income households can access the supply of middle-market units more easily than low-income renters. This competition can boost up middle-market rents, but can also give incentive for apartment owners who, seeing growing demand among high-income households, can transition modest-priced units to higher rent levels, thus depleting the supply of lower-rent units and putting further pressure on low- and middle- income renters. Such upgrading has contributed to the loss of 2.8 million low-cost rental units nationwide since 2000.

Growth in high-income renters limits the ability of high-end rental construction to ease pressures for lower-income renters.

With vacancy rates at their lowest point since the mid-1980s, there are few units available at any price point, so growth in renter households is increasingly made possible only by building new rental units. Rents for new rental units are high, and therefore only available to renters with relatively high incomes. Nationwide, the median asking rent of units built in 2019 was roughly $1,600 a month, which requires an income of $64,000 per year to be affordable under the 30 percent of income standard – well above the 2018 median renter income of $40,000. In the Northeast, the median asking rents were more than $2,300 per month, which is only affordable to a household with an income over $92,000.

The fact that new rental units are expensive is not news, although as our America’s Rental Housing report notes, new units are getting more expensive relative to the existing rental stock – with new unit rents rising from $350 per month higher (48 percent) than the overall median contract rent in 2011 to $700 higher (78 percent) in 2018.

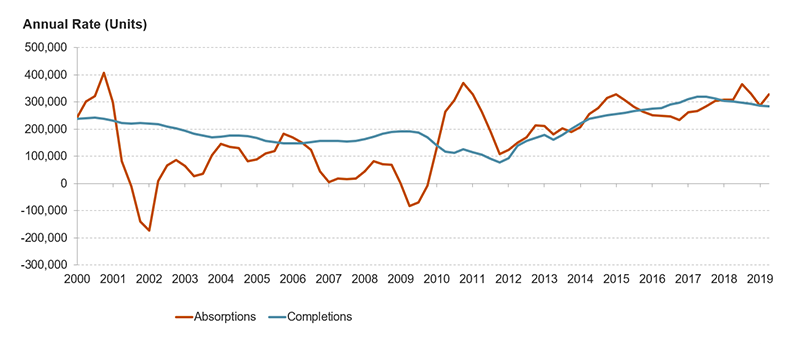

What is different about the recent dynamic is that new construction is accommodating a growing number of high-income households, but just barely. Indeed, despite the relatively high rents, the number of new apartment units being added each month is scarcely keeping up with growth in units rented out, or “absorbed” by new renters (Figure 2). When new construction is only just meeting demand from new high-income renters, it means that, in effect, new high-end units are being rented out by new, high-income renters, rather than by current high-income renters trading up to a newer unit, and therefore fewer old units are left to ‘filter down’ to a lower-income renters.

Figure 2: Nationwide, New Apartment Supply is Just About Meeting the Growth in Demand

Notes: Professionally managed apartments.

Source: JCHS tabulations RealPage data.

Growth in high-income renters can mask growing difficulties faced by low-income renters.

Growth in high-income renter households can make it harder to see the growing difficulties faced by low- and middle-income renters in basic statistics. When new renters are added at the top of the income distribution, the change in the mix of renters can make it appear as though renter incomes are rising, even if incomes of lower-income renters themselves are stagnant or falling. For example, aided by the addition of higher-income renters, our analysis of CPS data show that the real median income of renter households increased 13 percent over the past 10 years, while the median income of renters in the bottom income quintile (the bottom 20 percent of all households) fell by 2 percent.

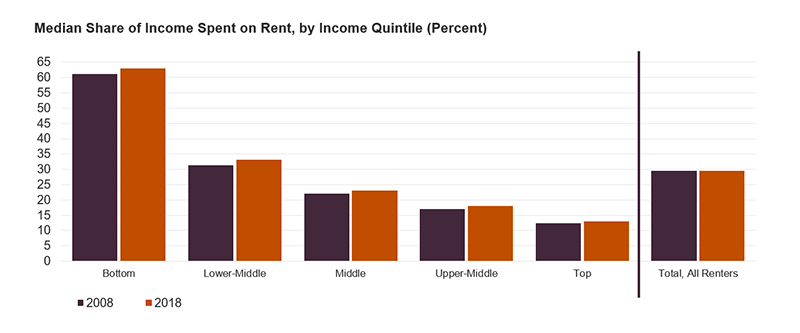

Growth in the number of high-income renters can also lead to misconceptions about trends in rental affordability. For example, between 2008 and 2018, even though rents were becoming less affordable for renters across the income scale, the increase in the number and share of high-income renters (whose median spending levels are lowest) brought down the average, making it appear that affordability levels were unchanged for renters as a whole (Figure 3). Specifically, we see that for renters as a whole, the median share of income they spend on housing was unchanged between 2008 and 2018 at 29.5 percent. However, during that time, rent spending increased from an already-high 61 percent to 63 percent of incomes for lowest-income renters in the bottom income quintile, and from 31 percent to 33 percent of incomes for renters in the second-lowest income quintile. In fact, the median share of income spent on rents increased for all income groups, with the lowest income groups registering the largest increases.

Figure 3: Growth in High-Income Households Can Make Burdens Among All Renters Look Unchanged Even as Rents Are Getting Less Affordable for Those with Modest Incomes

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey

Growth in high-income renters signals that access to homeownership is being limited to all but the highest income households.

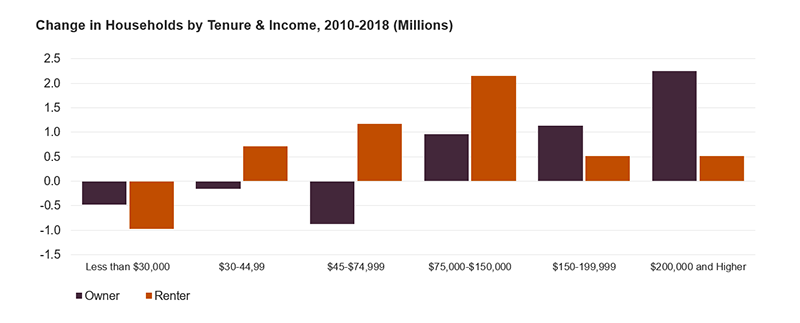

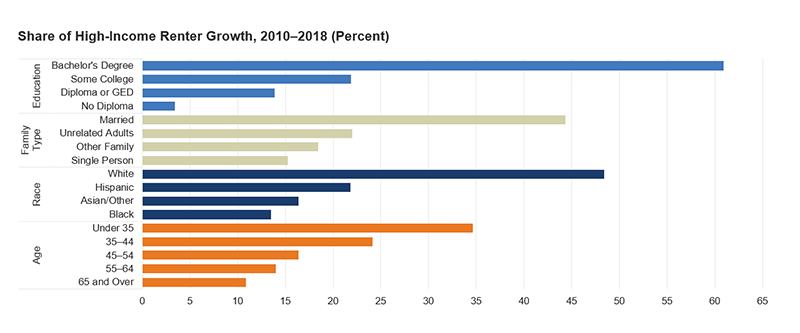

The last point to note is that renters with incomes of $75,000 – $150,000 accounted for most of the recent growth in high-income renters. Although these are relatively high incomes for renters, they are not the very highest income groups overall. In fact, growth in homeowner households since 2010 has been more concentrated among households with even higher income levels than growth in renter households (Figure 4). Indeed, fully 2.2 million of the 2.8 million growth in the number of homeowner households between 2010 and 2018 was households with incomes $200,000 or higher (while the number of homeowner households with incomes below $150,000 declined). The fact that homeowner growth is so highly skewed towards households at the extreme high end of the income spectrum suggests that at least some of the growth in high-income renters is due to access to homeownership being increasingly limited to all but those with the highest incomes, leaving more and more households whose incomes are well above the US median income still unable to buy homes. Growth in high-income renter households favors those with characteristics traditionally associated with first-time homebuyers, led by college-educated, married, non-Hispanic white households under 35 (Figure 5).

Figure 4: With Growth in Homeownership More Constricted to Highest-Income Households, the Number of Mid- to High-Income Renter Households Keeps Rising

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey

Figure 5: Most of the Growth in High-Income Renters Has Been Among College-Educated Households that Are Married, White, and Young

Notes: Incomes are adjusted for inflation using the CPI-U for All Items. High-income households earn at least $75,000 a year. Married families include married couple households with or without children. Other families include single parents. White, black, and Asian/other households are non-Hispanic. Hispanics may be of any race.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates.

Renter attitude surveys find that the majority of young renters still aspire to become homeowners, and report affordability as the major barrier to homeownership. Indeed, as detailed in our latest State of the Nation’s Housing report, the income needed to afford the median home price rose 26 percent from 2013-2018, to $67,300. In 2018, households earning less than $100,000 could not afford the median-priced home in over 13 metro areas, and would need to earn over $347,000 to afford the median priced home in the San Diego metro area – an area with a population of over 3.3 million. Since 2018, NAR data show the median US existing home sales price was up another 5 percent in 2019 and 7 percent year-over-year in January of 2020.

In conclusion, the growth in high-income renters across the US creates unique challenges for lower-income renters that can be understated or even missed in the aggregate statistics on renter affordability. Analysis of these challenges also shows how homeowner and renter markets are intertwined, and how affordability challenges faced by low- and modest- income renters are related to reduced homeownership opportunities among middle- and upper-income households. Ultimately, with high-end demand reducing the amount of rental units filtering down to lower-income households, or even reversing the flow by shifting more units to higher rents, building more housing to meet the needs of the middle of the market becomes even more necessary in order to increase supply and reduce affordability pressures on low- and middle-income renters.