Defining “Use with Caution”: How We’re Navigating New Census Bureau Data

Pandemic disruptions affected the 2020 American Community Survey (ACS) results so significantly that traditional 1-year estimates were not released by the Census Bureau. The Bureau did, however, release experimental estimates and products along with several tables and PUMS data for 2020 with a disclaimer to “use with caution.”

So what does “use with caution” mean to the research team at our Center? With help from the methodology paper published by the Bureau, we will share our understanding of this dataset and why we largely cannot use it for much of our housing research, and one way we will salvage some use.

To begin to understand the experimental ACS data, let’s first review the problems with the ACS survey in 2020. For several pandemic-related reasons, the ACS survey reached an unusually low number of people in 2020. Fewer people returned their surveys, which is understandable given that it coincided with the start of the pandemic. Additionally, a large number of people didn’t know they were in the survey; they were never notified, because initial survey mailings were halted during early 2020 shutdowns. And for addresses that were mailed a survey but failed to respond, the Census Bureau paused the normal in-person follow-up visits. These issues created two major problems:

Problem 1: The 2020 ACS Overestimates the Number of US Households

The first problem, which is not addressed by the experimental data, is that the 2020 ACS overestimates the number of households in the US.

Ordinarily, in-person visits are used to confirm that units are vacant, and not home to an occupant who simply failed to respond. Because the survey assumes all non-responses are occupied units until proven vacant with a follow-up visit, the 2020 survey underestimates vacant units and overestimates occupied units, or households. Additional steps were taken by Census in 2020 to determine vacancy of units in other ways but ultimately fewer units were able to be proven vacant than under normal circumstances, and therefore the number of occupied units jumps from 122.8 million in 2019 to 124.3 million in 2020, which is spuriously high and not comparable to estimates from previous years.

So “use with caution” in this case means we cannot use the 2020 ACS to compare the number of households in 2020 with levels from earlier years to look at household growth through 2020, or growth in any subgroups of households like renters or homeowner households.

It is important to note that the experimental weights do not account for this overestimate of total households in 2020. In fact, in the appendix table of the Census methodology paper we can see that the total estimated number of households in 2020 (124.3 million) is the same in the experimental weights and the raw original weights. So any measure or comparison that involves growth in households or specific groups of households between any previous year and 2020 are not reliable.

Problem 2: The 2020 ACS is Not Representative of US Households

The second problem that stems from the low response rate and lack of follow-up visits is that the 2020 ACS sample was not representative of the US population. The data undercounts groups that were more likely not to respond to the survey, which was often those most affected by the pandemic: lower income households, households of color, renters, households in multifamily homes, those with less than a college degree, and other groups not fully identified. While there is always unevenness in who responds to surveys in any given year, the differences in 2020 were beyond what is expected and addressed by normal survey weighting procedures. It is this pandemic-driven unevenness in the survey that the experimental weights were devised to address.

The experimental weights use additional administrative data and alternative methods to re-weight the sample to correct for errors introduced by the small sample size. For some variables, such as income and homeownership rates, the experimental weights appeared to produce more reliable estimates, but for other variables such as employment, marital status, and educational status, questions remain.

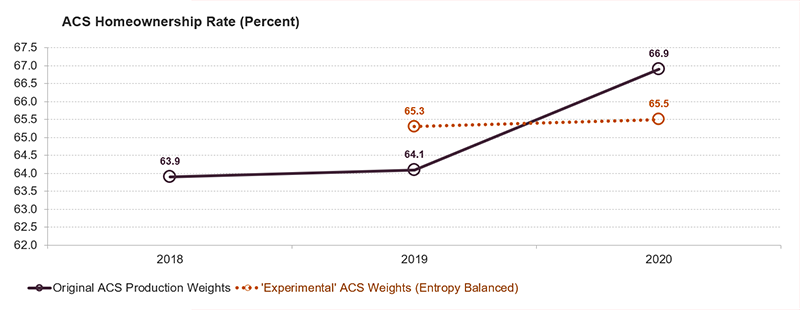

But there is another more fundamental issue with using the experimental weights, which we can see in the chart below. Even when the experimental data appear to generate more reasonable results, they are inconsistent with previous survey results because the data do not use the same weighting methodology used in previous years. If ACS results from previous years were re-calculated using the experimental 2020 weighting methodology, they would be different. This is why the results are “experimental” and not comparable to results from 2019 or earlier years.

Figure 1 provides a good example of the consistency problem and why the experimental results from 2020 should not be compared to results from 2019. We see that the survey’s homeownership rate for 2020—which was overinflated by the oversampling of higher income households—was reduced from 66.9 percent under the normal, production weights to 65.5 percent under the experimental weights. The 2020 homeownership rate goes from a full 2.8 percentage points higher than the 64.1 percent published rate in 2019 to just 1.4 percentage points higher, which seems like a reasonable increase in a year. However, there is a new problem, as shown in Figure 1. When experimental weights are created for the 2019 data, the homeownership rate increases from 64.1 percent to 65.3 percent. So instead of suggesting a 1.4 percentage point increase in homeownership rate over the past year, an apples-to-apples comparison between similarly weighted surveys from 2019 and 2020 suggests the increase in homeownership rate was just 0.2 percentage point. So even when experimental weights appear to create more reasonable estimates for 2020, they are not comparable to rates from 2019 data unless that data are also transformed using similar weights.

Figure 1: The ‘Experimental’ Weighting Process Used in 2020 ACS Would Also Raise the 2019 Homeownership Rate Estimate and Therefore Reduce the Observed Change in 2019-2020

Sources: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2018 ACS. Modified reproduction of Figure 12, Jonathan Rothbaum, Jonathan Eggleston, Adam Bee, Mark Klee, and Brian Mendez-Smith, "Addressing Nonresponse Bias in the American Community Survey During the Pandemic Using Administrative Data," US Census Bureau, 2021.

Re-Defining "Use with Caution" More Specifically

Knowing that the 2020 Experimental ACS have both size and comparability issues, here’s how we are using the data in our research.

First, what we are not doing: we are not comparing results under the 2020 experimental ACS with those from earlier years of ACS or using 2020 ACS for trends or changes. For one, the household counts are spuriously high for reasons explained above. Additionally, even though the estimates (rates, ratios, medians, etc.) in the 2020 Experimental ACS might appear comparable to previous surveys, they are not because the survey was produced using a different methodology.

The inability to compare 2020 ACS results to previous years limits our use of the dataset severely. Indeed, even if we don’t do so directly, our results will be viewed in context with those from previous years. However, one way to get more use out of the 2020 ACS data would be if the Census Bureau were to release previous years of ACS data with the experimental weights used in 2020, such as the Experimental 2019 data used in the Census’s methodology paper. Such data exists but is not available to the public. Wider availability would benefit researchers who could then see 2019 and 2020 data on a more even playing field and better gauge changes to various rates such as homeownership and cost burdens for various groups. Even with this approach, however, due to the issues with the overall household counts for 2020 ACS which were never resolved, we still could not use ACS for estimates of household growth.

For lack of better alternatives, when we need to compare characteristics of groups in 2020 alone and not compare to other years, we will use 2020 ACS in a sparing way that acknowledges there are still unresolved issues. As the methodology paper concludes, “data quality issues remain for some topics, such as employment, marital status, educational attainment, and Medicaid coverage.” This means that whenever possible, we will try to control for these issues. So, for instance, in looking at cost burden rates by race we might look at cost burden rates by race and educational attainment.

In conclusion, the experimental data are interesting, but without the ability to compare or contextualize the results to those from previous years, their uses are extremely limited. If Census were to make publicly available these earlier data with weights that make them comparable to the 2020 data, more housing researchers might be able to gain insights on the vast changes that occurred to people and households in 2020.