Using Community Income Levels to Help Tenants Get Emergency Rental Assistance

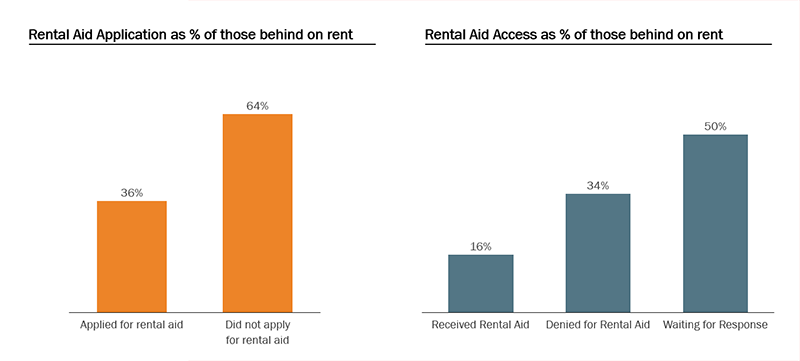

Despite improving economic conditions, millions of Americans – including a disproportionately large number of BIPOC and Latinx households and families with children – are at risk of eviction and displacement. An unprecedented $46 billion federal investment in Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) was supposed to help address this problem. However, for a variety of well-documented reasons, less than 15 percent of that money had been distributed by the more than 400 jurisdictions distributing ERA as of August 2021. As a result, according to tabulations of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, 50 percent of rental-aid applicants are awaiting a response. Another 33 percent have been denied. Making matters worse, 64 percent of those behind on rent have not applied for assistance.

Figure 1. Census: Renters Behind on Rent Struggle to Access Rental Assistance

Source: Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Week 37 Table 3b

As co-founder and COO of the COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project (CEDP) – work I began as a 2020 Summer Fellow in Housing and Community Development for the Center – I not only have seen these problems firsthand but have been developing ways to address them.

CEDP, which began as a community organizing and data project, has become a broader housing stability organization with contracts to provide ERA assistance in 62 of 64 Colorado counties. CEDP now offers a continuum of care for 300-400 renter households per month, including providing urgent, sometimes overnight, processing of rental assistance for tenants facing eviction. As a part of this continuum, CEDP also offers legal aid and rehousing services to stabilize families for whom rental assistance alone will not work.

Like many other entities distributing ERA funds, our efforts have been hampered by a variety of factors. Many renters do not know about the program. Those who do apply need at least six documents to complete an application: identification, proof of income, amount owed, and residency (leases), as well as program agreements, and W-9 forms. This documentation burden—particularly proof of income—falls hardest on communities of color, people with disabilities, and those who do not speak English. Tenants with the proper documents still face delays in processing their applications.

For those who are on the eviction clock, these problems metastasize. If rental assistance is not provided before an eviction occurs, families face monumental consequences. Evictions are linked to job loss, homelessness, chronic illness, poor learning outcomes for children, and now death from COVID-19. Recognizing the impact of the delays on families, the Biden administration announced a major effort to speed up the rental assistance process in late August. According to guidance provided by the Treasury Department, instead of requiring tenants to document their income, agencies distributing ERA funds can allow tenants to attest that they are unable to provide this documentation, use the fact that applicants’ incomes have already been verified by another public program, or use any reasonable fact-specific proxy (FSP) for household income, such as data regarding average incomes in the household’s geographic area.

Most jurisdictions administering ERA have been slow to adopt guidelines that allow applicants to self-attest without providing additional documentation. Many have not broadened their rules largely because they are overburdened. Their technology partners like Neighborly (a primary platform used by ERA providers) have also been slow to implement user-friendly product updates that allow tenants to self-attest directly in the application. Moreover, many agencies are reasonably wary of self-attestation because key staff recall absorbing losses during audits of Great Recession mortgage relief programs.

Treasury’s third option – an inclusive fact-specific proxy – offers an express lane to bypass these obstacles. Agencies have broad latitude to use FSPs, which can eliminate back-and-forth for tenants, shifting documentation burdens almost entirely to property owners—who should have documents. Connecticut and Colorado have directed agencies to use Qualified Census Tracts (QCTs) as their proxy to verify tenant income. A QCT proxy allows grantees to income qualify tenants in tracts where more than 50 percent of households have incomes below 60 percent of the area median income or a poverty rate of 25 percent or higher.

While this is a common and reasonable standard for income estimation, I believe ERA programs should instead use the more expansive Low-Income Community (LIC) designation. Congress has authorized several federal initiatives, including New Markets Tax Credit, Targeted Economic Injury Disaster Loan Advance, and the Opportunity Zone programs, to use LICs to identify under-resourced areas. LICs have a poverty rate greater than 20 percent or a median income that is less than 80 percent of the median income in the metropolitan area (or the state, if the tract is not in a metropolitan area).

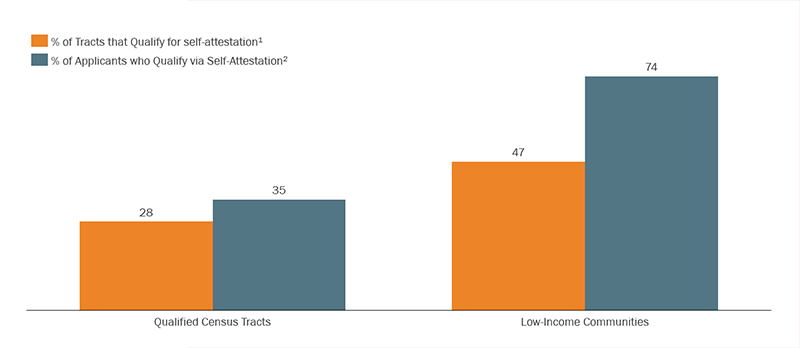

Figure 2. Denver Data: Using the Low-Income Communities as Fact-Specific Proxy Doubles Percent Who Qualify for Rental Aid Using Self-Attestation

Analysis by Nikki Talerman; Sources: 1. Census Bureau QCT and Income data, 2. Sample of 500 CEDP clients in Denver qualification for self-attestation based on proxies

Making this shift would greatly expand the number of people who could more easily get ERA funds. For example, in Denver, which worked with CEDP to adopt this proxy measure, 47 percent of the tracts are LICs compared to only 28 percent that are QCTs. As a result, while 35 percent of 500 applicants for assistance from CEDP had qualified for self-attestation under the QCT metric, 74 percent qualified after the shift to QICs. The metric, moreover, is easy to implement. If reviewers can find the tenant’s address in this Small Business Administration look-up tool, they can take a tenant’s income attestation at face value. Assuming they can get needed information from landlords, they can immediately cut a check to stabilize the household.

At the current pace, it will take 16 months to expend remaining ERA funds. Using the LIC proxy (or similar reasonable proxies) will speed up rental aid distribution for families who need funds to arrive before their court dates. At scale, it could speed up a system designed to prevent millions of evictions and displacements.

Special thanks to Nikki Talerman for the data analysis and thought partnership.