National Politics, Neighborly Politics: The Impact of Trump’s Election on a Detroit Community

While some researchers have studied how historical community transformations and neighborhood contexts can shape voting patterns, few have examined what happens locally after votes are cast. In a paper recently published in Sociological Forum, I show how Donald Trump’s 2016 election impacted residents’ expressions and experiences of racism in Brightmoor, a majority black, minority white, poor Detroit neighborhood. This political moment of heightened right-wing populism shaped how pro-Trump whites and black residents started to navigate local interactions and geographies.

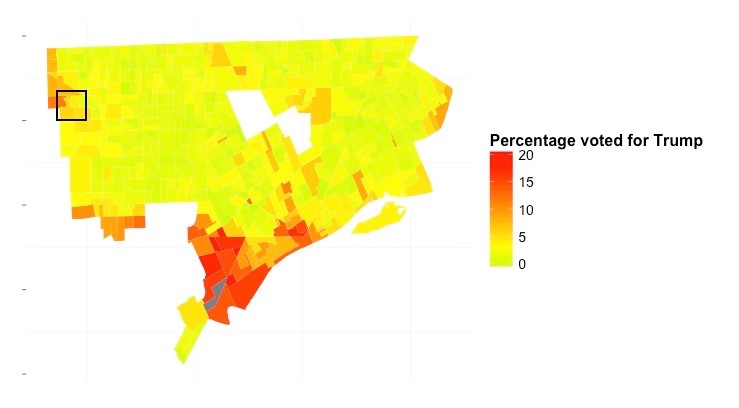

In National Politics, Neighborly Politics: How Trump’s Election Impacted a Black and White Community, I draw on three years of ethnographic fieldwork conducted while I lived in Brightmoor, a neighborhood in Detroit’s outskirts that, like most of the city, had dramatically transformed in recent decades. Since 1980 the neighborhood had lost over half its residents, while it turned from all-white to 80 percent black. By 2016, every other property in the neighborhood was a vacant lot and every third house stood empty. Every other resident lived in poverty. Most white residents who remained were middle-aged to elderly poor homeowners who lived near the suburban border, where 25 percent of residents were white. In these precincts, 5 to 11 percent of the vote in the 2016 elections went to Donald Trump, compared to 3 percent Detroit-wide. In bordering suburbs Redford and Livonia, Trump received 27 percent and 51 percent of the vote, respectively. While only a minority of Brightmoor residents then supported Donald Trump, his election significantly affected the neighborhood.

Figure 1: Voting in 2016 Presidential Elections in Detroit and Brightmoor

Note: Brightmoor marked in black in northwest Detroit

Source: Author’s map (Ggplot2, R), based on Michigan Secretary of State 2016 data

On the one hand, I found that local white Trump supporters tried to separate xenophobic ethnonationalism from racial politics. Trump’s national surge empowered many to broadcast anti-immigrant sentiments in public spaces and online. At the same time, they remained mostly silent on Trump’s racial politics and remained careful to not be seen as “racist” against black people: both in their current practices and as they talked about their historical experiences with white flight and busing in Detroit. I also found that Trump’s election had made minorities that were targeted under Trump’s politics – notably Syrian refugees and undocumented immigrants – hyper-visible for these voters. Some even started to see these minorities in the neighborhood when they were not physically there. I call this “the Trump lens,” a new way of seeing shaped by Trump’s politics. For instance, Janette, a 53-year-old white resident had organized her mental map of metropolitan Detroit into places with and without Muslims. She said: “You roll through downtown Franklin, it’s all you see, is women walking around in them, what do they call those things, those black things? [Interviewer: Burkas?]. Yeah, Franklin is full of them. It’s not just Brightmoor. They’re all over. I refuse to go to Hamtramck. You know, or Dearborn. Those are no-go zones.”

On the other hand, black residents equated anti-immigrant ethnonationalism to anti-black racism: rejecting Trump supporters’ attempts to separate these. When they talked about Trump’s anti-immigration policies, many gave examples of historical anti-black racism to invoke their commonality. Shantell, a black, 59-year-old veteran, even put herself and other African-Americans on the “wrong” side of Trump’s border wall, when she said: “He trying to put up the wall. In that case, you’re just saying you’re gonna push all that’s black and whatever else to one side and put up a wall for us.”

Moreover, I show how Trump’s election also affected how black residents interacted with white Detroiters and suburbanites. Historically in Detroit, black residents had little difficulty identifying who was racist and who was not, as individual racism was often extremely overt – from neighbors spitting in their yard and racial violence to being denied work and housing. Many contemporary racist interactions, though, also involved tension and ambiguous moments of disrespect. To interpret and avoid these interactions, some black residents now started to use the categories of “Trump voter” and “places where Trump voters live” as markers of potential racism. Black residents, then, had also developed a “Trump lens” in this historical moment, though it was one oriented towards identifying Trump voters.

This research not only illustrates the importance of documenting the local impacts of national politics, but also offers two important lessons that are particularly relevant as we approach the 2020 presidential elections.

First, having a president who openly expresses anti-black racism does not need to be mirrored at the local level. Instead, I found that supporters attempted to separate their support for Trump from expressions that could possibly be seen as anti-black racist. For instance, they remained silent on Trump’s racial politics in public, while vocally endorsing his anti-immigration policies. In my paper, I show how these attempts at boundary work, of separating the two, failed in the eyes of black residents, as they connected contemporary ethnonationalist policies with racist histories, such as slavery and Jim Crow era violence.

Second, we see a stark divergence in mental maps and the experienced worlds in which Trump voters and minorities lived after Trump’s election. The Trump lens of Trump supporters tended to reinforce itself as a kind of cognitive bias, as they started to foreground and even imagine seeing minorities consistent with their politics. Moreover, while the heuristic of “Trump voter” may be helpful for minorities to anticipate and make sense of at-times ambiguously racist interactions, it also clashed with how Trump supporters saw themselves: as they were overtly xenophobic against immigrants but wished not to be seen as racist. As a result, it also represents a source of distancing, misunderstanding, and potential resentment.