When Family Can’t Care for Older Adults During COVID-19, Who Will?

As we’re learning more each day, the coronavirus pandemic poses a dire threat to America’s 1.4 million nursing home residents, but it also impacts the welfare of the 50 million older adults living in houses and apartments across the country. While COVID-19 poses a high risk of harm to healthy older adults, those with complex health conditions experience even greater risk and are also more likely to rely on an informal network of caregivers to maintain independence. The pandemic can disrupt this caregiving network and destabilize the living arrangements of millions of older adults, at a time when some states are working to assist families with the decision of whether or not to move congregate care residents into a family member’s home.

According to the Institute on Disability, about 17 million adults aged 65 or older experience difficulties that require support, including sensory deficits, ambulatory or cognitive impairments, or challenges with self-care or independent living tasks. Without adequate assistance, these difficulties can impact health, increase the risk of hospital use, and destabilize housing. Caregiving for age-related conditions encompasses a broad range of activities from in-home cooking or housekeeping, community errands like banking or shopping, or help with daily personal care and grooming. Along many pathways, the novel coronavirus threatens informal care provision and destabilizes the independence of older adult households.

Compared to other countries, the US relies more heavily on informal care. In 2017 and 2018, more than 40 million Americans provided unpaid, informal care to an older adult and 80 percent of this assistance was provided to someone living in a different household. In 2015, family caregivers delivered an average of 34 hours of care each week, with one in four spending more than 40 hours each week. Since this support is informal, it relies on a private agreement and on caregiver capacity. Informal care relationships are not catalogued or enforced by any government entity. Despite the scope of informal caregiving, it is difficult to quickly locate or supplement these arrangements during a time of crisis.

The pandemic impacts networks of care along various avenues. Caregivers who become sick with the coronavirus must interrupt the care routine. With 8.6 million caregivers aged at least 65 years, many will choose to shelter at home for their own protection. A caregiver might also be pulled away from support tasks by a sudden loss of childcare, a major economic hardship, or a household illness. Finally, caregivers without formal medical training or access to personal protective equipment may choose to protect the older adult by minimizing contact. In combination, these factors threaten many individual caregiving relationships and lay the groundwork for large sectors of the caregiving network to breakdown.

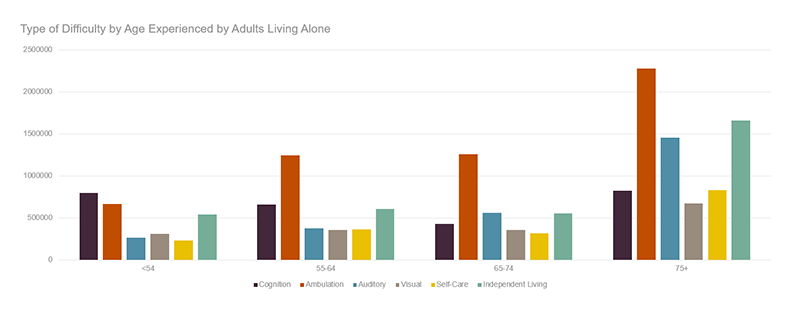

A caregiving disruption would be particularly difficult for to an older adult living alone. As noted in an earlier blog, single-person households experience higher needs and also have fewer resources to meet those needs. According to tabulations from the 2018 American Community Survey, 5 million adults, or 40 percent of all older adults living alone, experienced at least one difficulty that could suggest a need for care. Nearly 7 out of 10 were women and their average age was 79 years. Both the proportion of people living alone and also proportion of people experiencing difficulties increased with age. Half of householders 75 years or older and living alone experienced at least one difficulty. Ambulatory challenges were most common, reported by 3.5 million people living in these households, but many also experienced independent living and self-care difficulties. Difficulties were particularly linked to age. While 16 percent of single-person households older than 65 experienced independent living difficulties, 24 percent of these households 75 or older experienced such challenges. In total, 3.3 million single-person households aged 65 or older specifically experienced a self-care or independent living difficulty in 2018.

Figure 1: With Increased Age, More Residents of Single-Person Households Experience Difficulty

Notes: Individuals may appear multiple times if they report multiple difficulties.

Source: Tabulations of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2018.

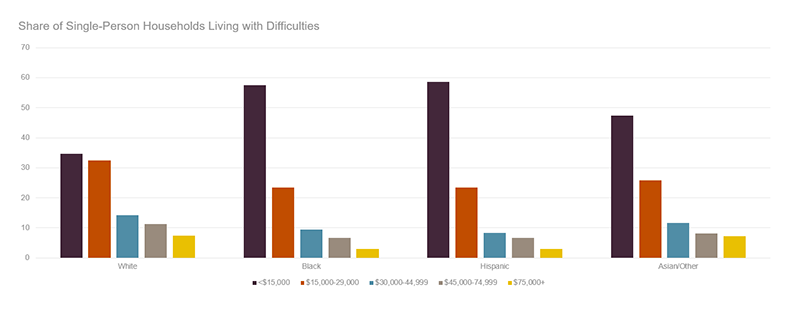

Finances introduce additional precarity to this vulnerable group. Privately funded formal homecare is extremely expensive, averaging more than $4,000 per month nationwide in 2019. Yet in 2018, more than 70 percent of older single-person householders with a potential care need had less than $30,000 in income. Housing costs further reduced capacity to hire a caregiver. The majority of this group paid rent or a monthly mortgage in 2018, and more than half were either moderately or severely burdened by housing costs. Racial and ethnic disparities deepen financial disadvantages as more minority older adults with care needs lived with lower income. While 34 percent of white single-person older adult households experiencing a potential care need had $15,000 or less income in 2018, 58 percent of black households, 59 percent of Hispanic households and 47 percent of Asian households of this description lived in this income strata. Inadequate financial resources reduce access to privately funded home care that could be used to compensate for a loss of informal care.

Figure 2: Single-Person Households 65 and Older Living with Potential Care Need Are Largely Low Income, but Disparities Exist by Race and Ethnicity

Source: Tabulations of US Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2018.

Public options are limited. State funds and Medicaid Home and Community Supports waiver services, the primary public providers of in-home supports for low-income older adults, have waiting lists in most states. Medicaid-funded nursing home care is available to those who meet level of care and income eligibility, but these restrictive environments are not appropriate for most community-dwelling older adults. More foundationally, the health risks of entering congregate care is very high during this COVID-19 outbreak. As a result, many who lose unpaid supports due to the novel coronavirus may be left with few alternatives. Living with unmet needs puts both health and stable housing at risk. Public resources must scramble to fill these gaps left by the disruption of the informal care-force.

A comprehensive policy response includes both resource infusion and communication. A variety of short-run public investments are needed to innovate and expand services and to ensure access to nutrition, personal care, medical, and mental healthcare. Supports for existing low-income service recipients are restructuring to promote social isolation. For instance, senior centers that remain open have transitioned from congregate meals to pick up or home delivery models. Rapid changes have also occurred in medical care delivery. While only 21 state Medicaid programs reimbursed telehealth for patient monitoring last year, all states now offer some Medicaid reimbursement for this mode of access. This reduces transportation burdens. New service options are also offered to some Medicaid home care recipients. For instance, California, Mississippi, and Colorado have authorized payment to some family care providers. This could promote stability for existing service recipients.

Public services must also expand to support older adults with slightly higher income who had not previously relied on formal care. With the federal emergency declaration, CMS has increased the pool of people who qualify for home care. Many restrictions for home care waiver services have been lifted and, to recognize COVID-19 related social isolation. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has expanded the definition of “homebound.” While about half of states have relaxed stringent limits and service guidelines for existing service recipients, states are not yet expanding access to new recipients. At this point, states bear a large financial cost for service expansions. Still some states, such as Massachusetts, have made a financial commitment to expand access to non-Medicaid funded care.

It will be difficult to locate the population that is not already receiving services. Existing bodies, such as Area Agencies on Aging, are critical coordinators to promote interagency education, build referral networks, and ensure there is “no wrong door” to reach support. Any older adult seeking assistance from any agency should be informed about other available resources. Organizations can also reach out to caregivers directly. For instance, the Family Caregiver Support Program in Massachusetts provides a platform of outreach to many informal caregivers. States even partner with large employers to disseminate information, as some organizations already offer caregiver support resources in order to mitigate caregiver burden for their employees. To manage future crises, states should consider the feasibility of a centralized communication mechanism that links to all caregivers and care recipients. Models such as dementia care registries facilitate efficient disaster response for all who opt in.

Public, private and nonprofit resources must expand well beyond their existing purview. The novel coronavirus will lay bare a deep reliance on informal, unpaid care for older adults and expose the consequences of a weak safety net. The health and housing stability of millions of vulnerable older adults depends on a well-resourced and coordinated public response.