What Strategies are Needed to Implement Energy Retrofits Equitably and Practically?

The recent Supreme Court decision limits the immediate ability for the federal government to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. There are other tools available, but the critically important efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from existing homes will fail unless they are done in ways that consider the nature and structure of the highly fragmented remodeling industry, and the diversity of household needs. With 20 percent of US greenhouse gas emissions directly attributed to housing—the equivalent of the sixth largest global emitter—most of the existing housing stock needs massive transformation to become more energy-efficient. Current energy retrofits are known to reduce individual home energy use by 30 to 70 percent. Transforming residential energy use to net-zero carbon through a combination of property-level renewables, electrification, and energy-efficient retrofits is aspirational, but increasingly attainable.

For a variety of reasons, getting the remodeling industry to do this work will be challenging. The sector is fragmented and its size and output are at an all-time high. In addition, the diffusion of energy-related improvements and replacements depend on the availability of products (ideally as less efficient products fall out of the market and homes need replacements). It also depends on owners’ willingness to invest in new products, knowledgeable and experienced professionals who can install and show people how to use them, and finally, the willingness of homeowners and renters to use and maintain new systems.

All these factors change over time and place, but they must align to accomplish our collective goal of an energy-neutral housing stock. Indeed, the Remodeling Futures Program is committed to pursuing new areas of research to better understand the market challenges and opportunities for home retrofits that improve the energy-efficiency of the housing stock.

Can the remodeling industry shine the right light onto energy retrofits?

Current and proposed investments in energy remodeling as a discrete objective will be met by an industry at nearly peak production levels and with historic input shortages. Our latest Leading Indicator of Remodeling Activity (LIRA) suggests that homeowner spending for improvements and repairs could grow 17 percent this year with total market spending on the owner and rental stock surpassing $500 billion. Indices show that sales from building material and supply stores and aggregate remodeling labor hours are at all-time highs. In short, residential remodeling is a huge sector, and continues to expand under current housing conditions and with only modest energy-related activities.

At the same time, property owners are increasingly choosing the professional remodeling and repair workforce for critical upgrades and home maintenance. The ostensible benefit of this reliance on skilled tradespeople is that newer technologies and products such as those that dominate much of the residential energy technological field are more likely to be installed accurately and according to technical specification.

But the downside to this shift is that remodeling contractors are more likely to focus on higher-margin projects during market upswings like the one we are experiencing. Further, and despite its size and importance, remodeling remains one of the most fragmented and geographically idiosyncratic of sectors within an already fragmented construction industry. Even though there has been some consolidation in the homebuilding industry and that has brought some standardization of technical skills and reaping of scale economies, most of the remodeling market’s pool of providers is still composed of smaller organizations working in different local markets with variable rates of growth.

Fortunately, constraints in the remodeling industry also present strategic opportunities. Home improvements vary by category (i.e., discretionary versus replacement) and project type (e.g., roof replacement, kitchen remodel, etc.) and energy remodels can be mapped against a broad range of projects. For example, roofing replacements could support photovoltaic installation and garage or carport additions might allow for electric vehicle charging.

Who wants energy improvements? And which homeowners need it?

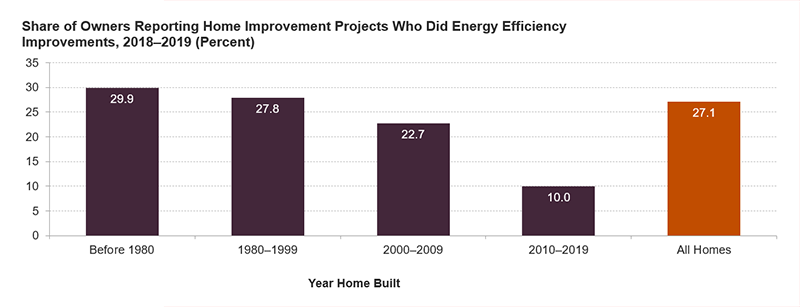

Several studies suggest a disparity in the take-up of energy retrofits and the programs to financially incent them. A fundamental factor in this disparity is the quality of the home itself—especially how old it is. As homes age, they require more maintenance and the replacement of whole systems and appliances. The same holds true for energy improvements, but with the added contribution of energy code rigor over time, which has led to newer, vastly more efficient homes. As such, homes built before the first energy codes of the 1980s and certainly before the first rigorous energy code of the 2011 cycle, are more likely to need energy improvements (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Remodeling for Energy Efficiency Increases with Age of Homes

Source: JCHS tabulations of HUD, 2019 American Housing Survey.

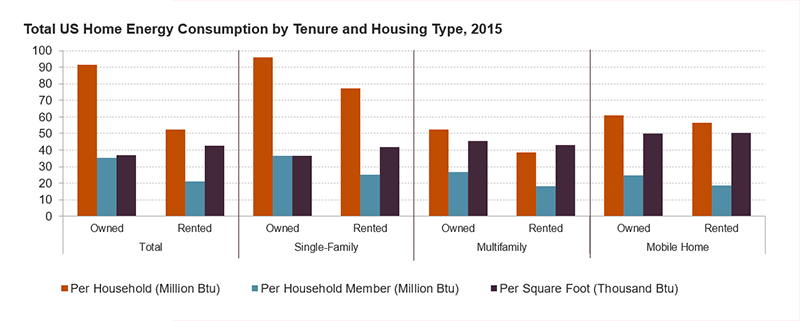

But other housing stock and household characteristics matter. For example, households in single-family homes consume significantly more energy per household and household member than multifamily and mobile homes (except for smaller multifamily properties with 2-4 units, that are often energy inefficient). Also, owners of all housing types consume more energy per household and member than their renter counterparts (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Homeowners Consume More Energy Compared to Renters Across All Housing Types

Note: Single-family units include attached and detached, and multifamily includes apartments in buildings with 2 or more units.

Source: JCHS tabulations of U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2015 Residential Energy Consumption Survey HC Table Series.

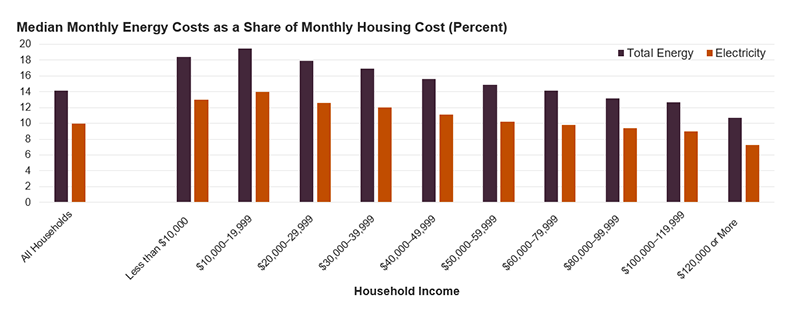

Lower-income households also consume less energy compared to wealthier ones, yet the cost of a unit of energy is uniform. Consequently, low-income households pay a higher portion of their monthly housing costs in energy bills (Figure 3). This disparity correlates with other household demographic and geographic characteristics. Lower-income households with older adults and those with children or members with physical disabilities are particularly energy-burdened. Low-income homeowners, who often lack the resources needed to pay for basic repairs, are less likely to have the funds for energy retrofits (even if those investments might reduce their long-term energy bills).

Figure 3: Energy Cost Burdens are Greatest for Lower-Income Households

Notes: Total energy costs include electric, gas, oil, and other fuels (i.e. wood, coal, kerosene, or any other fuel). Data are for occupied units that use and pay for one or more types of energy, where the energy cost is not included in rent, site rent, condo fee, or other fee, or included in another utility cost.

Source: JCHS tabulations of HUD, 2019 American Housing Survey.

The light ahead

The need for energy retrofits of the US housing stock has never been greater. The country’s international climate commitments as well as our domestic obligations to energy equity have colluded to make this a national imperative. Only new homes, which make up 1 percent of homes in any year, are affected by building codes, making efforts to increase building code requirements helpful, but limited. While research, development, and deployment have measurably changed the efficiency of new housing, the energy conditions in existing homes are daunting.

With the passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act last November, the budget of the US Department of Energy’s Weatherization Assistance Program increased ten-fold. This investment is a critical component for addressing our national climate goals. They also support the current Justice 40 goals of uplifting historically underserved and disinvested by ensuring our nation’s ability to provide a safe, decent, and affordable home for every American, including those without the means to do so on their own. Lowering the costs through a range of policy, programs, and requirements will also help, such as the White House’s recent invoking of the Defense Production Act to accelerate the production of clean energy technologies. The urgency requires an expansion of residential efficiency and renewable energy programs along with innovations in other interventions such as electrification. Ultimately, however, the policies and programs that promote energy improvements in existing homes must incent remodelers and property owners alike.