What Financial Resources Have Renters Tapped During the Pandemic?

To keep up with housing payments during the pandemic, renters tapped a wide range of financial resources, according to a new paper published as part of the Housing Crisis Research Collaborative. Indeed, renter households who lost employment income engaged in complex financial strategies to meet their obligations, including using credit cards, savings, and borrowing from family and friends. The reliance on informal borrowing suggests that after renters exhaust their own resources, they turn to their social networks, extending the financial impacts of the pandemic beyond those directly impacted.

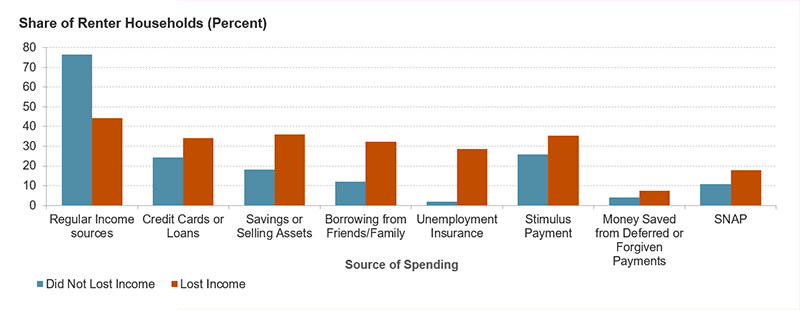

In “Making the Rent: Household Spending Strategies During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” we draw on the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey data from August 2020 through March 2021, a period when nearly 17 percent of renters were behind on their rent and 52 percent had lost employment income since the start of the pandemic. The households who lost employment income were naturally less likely to tap regular income sources like those received before the pandemic to meet their spending needs (44 percent) compared to those who did not lose employment income (76 percent) but were more reliant on other private and public resources, including credit cards, savings, borrowing from friends and family, and unemployment insurance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Renter Households That Lost Income During the Pandemic Were Much More Likely to Rely on Other Sources to Meet Their Spending Needs

Notes: Employment income losses occurred at any time during the pandemic.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau Household Pulse Surveys, August 2020-March 2021.

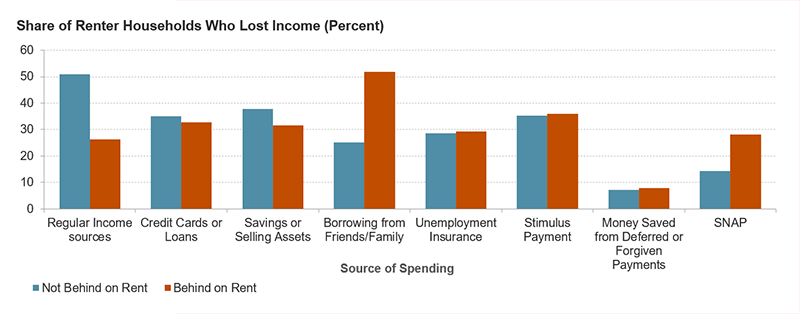

Among renters who lost income, households behind on rent used significantly different strategies to meet their financial obligations than those not behind. In addition to their more limited ability to tap regular income sources, renters who fell behind were far more likely to borrow money from family and friends (Figure 2). Indeed, renters who lost income and were behind on rent engaged in informal borrowing at twice the rate of those not behind on rent. These high rates of borrowing suggest that households behind on rent had fewer personal financial resources in the first place and may have quickly depleted the already meager financial resources they had. As a result, the financial impact of the pandemic extends beyond those directly affected by income losses and into their social networks.

Figure 2. Among Renter Households That Lost Income, Households Who Also Fell Behind on Rent Were Much More Likely to Borrow From Friends/Family or Use SNAP

Notes: Employment income losses occurred at any time during the pandemic. Households behind on rent reported that they were not caught up at the time of survey. Sample is cash renter households who lost income.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau Household Pulse Surveys, August 2020-March 2021.

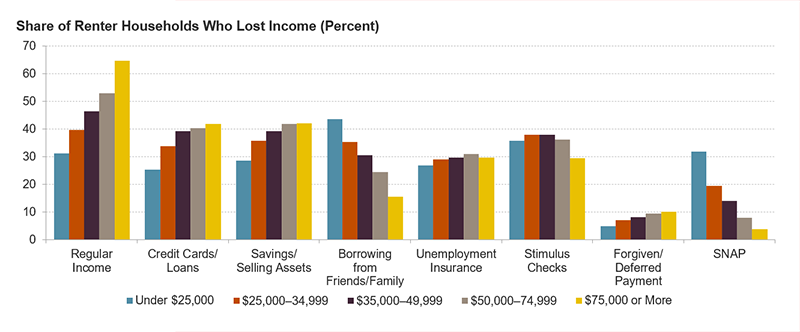

Spending strategies differed not only by payment status but by household income, which can dictate the financial resources households have access to. Among those who lost employment income, households making less than $25,000 were much less likely to use regular income sources, credit cards, or savings to meet their spending needs, likely because they lacked access to these resources (Figure 3). Instead, lower-income households were more likely to rely on informal borrowing from family and friends (35 percent for lower-income versus 16 percent for higher-income households) as well as SNAP (32 percent for lower-income versus 4 percent for higher-income households). As we show in the paper, Black and Hispanic renters—who have lower incomes on average because of discrimination in education and labor markets—engaged in similar spending strategies in response to a financial shock during the pandemic.

Figure 3. Lower-Income Households Were Less Likely to Rely on Regular Income and Were More Likely to Borrow

Notes: Employment income losses occurred at any time during the pandemic. Sample is cash renter households who lost income.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau Household Pulse Surveys, August 2020-March 2021.

Our findings indicate that the financial impacts of the pandemic are likely deeper than the estimates of rent arrears alone might suggest. The impacts extend beyond households who lost income and into the communities of those immediately impacted. As a result, broad-based cash-assistance programs like expanded unemployment insurance and SNAP benefits not only provide critical support for impacted renters but mitigate some of the broader financial harms. Still, renters who lost income and ultimately fell behind on rent despite extensive and complicated coping strategies remain among the hardest hit. For these households, emergency rental assistance remains crucial, but additional eviction diversion supports such as legal aid, help with moving costs, credit repair, and assistance with a deposit and other up-front costs for a new apartment might also be necessary to fully address the consequences of the pandemic’s financial fallout.