The Freddie Mac G-Fee Discount: Has the Single Security Eliminated It for Good?

When I joined Freddie Mac as CEO in 2012, I knew that, despite it being a giant company with $2 trillion in assets, it was nevertheless disadvantaged versus its main competitor, Fannie Mae, with its $3 trillion. The cost disadvantage – a one-third smaller base of revenue-generating assets to absorb fixed costs – was obvious. But what was not obvious to me was the endemic revenue disadvantage in that Freddie Mac was unable to earn as high an average g-fee (guarantee fee) on its book of single-family business, as Fannie Mae. As g-fees are the biggest source of revenue to the company, this was a significant disadvantage.

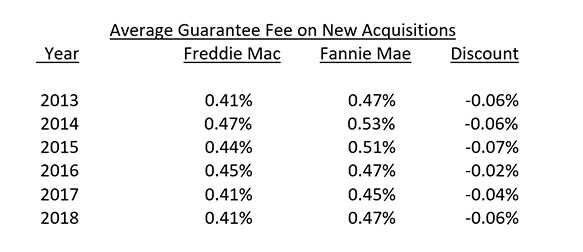

As shown below, in the last six years, the average g-fee on “new acquisitions” booked by Freddie Mac was always less than what Fannie Mae earned.

Source: Annual Financial Reports (Form 10-K) filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Now, there is definitely some “noise” in the average g-fee being reported. For example, Fannie Mae usually has a slightly riskier mix of business, which would translate into a slightly higher g-fee as both companies do risk-adjust pricing (i.e. charging higher rates for higher risk mortgages). Additionally, while a portion of the g-fee is paid on a per-annum basis, another portion is paid up front, so it is then amortized over the estimated remaining life of the associated mortgages. Because that estimate is always changing, as prepayment “speeds” vary over time as interest rates go up and down, it introduces volatility and noise into the numbers (and the noise can also reflect somewhat different methods of amortization between the two companies).

But over the six years shown above, the pattern is clear: Freddie Mac is averaging about 0.05 percent less on its $2 trillion book of business than Fannie does on its larger one. This is the Freddie Mac g-fee discount. And it was primarily attributed to the different trading liquidity of their respective mortgage-backed securities (MBS), as explained below.

This discount would roughly equal a missing $1 billion of revenue per year for Freddie Mac on a pre-tax basis, or roughly 10 to 15 percent of its entire corporate earnings on an after-tax basis. That’s clearly a material issue, despite the size of the discount – just 0.05 percent – seeming to be so small.

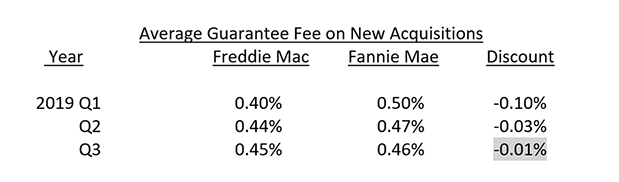

But with the introduction on June 3, 2019 of the “single security,” this discount was hopefully to be eliminated through a more efficient marketplace for GSE mortgage-backed securities. And the quarterly figures in 2019 seem to validate that the discount has, indeed, been substantively eliminated.

Source: Quarterly Financial Reports (Form 10-Q) filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Yes, in the first full quarter of the single security (Q3 of 2019) the discount is down to just 0.01 percent, which could easily be explained by Fannie Mae’s slightly riskier mix of business. It will take a few more quarters of such a minimal/nonexistent discount to be sure it is gone for good, of course, but the start is excellent.

The historic discount, in fact, was a quirk stemming from the two GSEs being supported by the government to the degree their liabilities are regarded as near-US Treasury quality. (This support was previously delivered before the government takeover in 2008 via the “implied guarantee” of the companies. Since then, it has been delivered by a legal agreement called the Preferred Stock Purchase Agreement.) Specifically, lenders can sell their loans to one of the GSEs and the interest rate on the mortgage – before any fees or markups the lender will add – is then fundamentally the sum of the interest rate demanded by investors to purchase the mortgage-backed security into which the loan was placed, plus the GSE’s fee charged to guarantee the credit of that mortgage to those MBS investors.

But the MBS rate has historically been lower for those issued by Fannie Mae than by Freddie Mac. This is not because Fannie Mae is a more creditworthy guarantor of MBS; in fact, history would say it has a slightly worse credit profile than Freddie Mac. Rather, because of the government’s support of the two companies, the creditworthiness of the GSE doing the guaranteeing is generally ignored by the marketplace. What is relevant to MBS investors is that the liquidity – the ability to buy and sell securities without moving the price much – is considerably greater for Fannie Mae’s MBS than it is for Freddie Mac’s.

And the nature of this kind of trading liquidity is that it is self-reinforcing: the more people trade the more liquid MBS, the more it has even higher liquidity. So, while Fannie Mae is 50 percent larger than Freddie Mac in terms of its balance sheet size, its trading volume is often cited as being 10 times as large as Freddie Mac’s.

Thus, Fannie Mae MBS have for a long time been purchased by investors to yield a bit less than the same MBS from Freddie Mac because investors prized that liquidity. To win business by competing with Fannie Mae, then, Freddie Mac had to charge a slightly lower g-fee so that the total of the two (the MBS rate plus the g-fee) was competitive. And this is the main underlying source of the Freddie Mac “discount” shown in the above tables.

The single security program implemented this past June gets around this by creating a single market in GSE mortgage-backed securities called the “Uniform Mortgage-Backed Security” or UMBS (the complex mechanism for how it does that is not relevant for this article). This means the total market liquidity of Fannie Mae plus Freddie Mac should apply equally to both GSEs and thus the MBS of both companies should trade at the same rate by having the same liquidity. Therefore, there should be no Freddie Mac extra yield required on its MBS rate, and no need for Freddie Mac to reduce its g-fee so that the total of the two is competitive. As a result, the 0.05 percent g-fee discount has collapsed to 0.01 percent in just the first full quarter of the single security implementation. This makes for a more efficient and competitive market in mortgage financing in the US, which was one of the main objectives of the single security project in the first place. And it seems to be working, hopefully permanently.