Renter Financial Distress Has Been Concentrated in High-Poverty Neighborhoods and Communities of Color

Renter households have been disproportionately harmed by the financial fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. But this financial distress was also highly geographically concentrated at the neighborhood level, according to a new paper published as part of the Housing Crisis Research Collaborative that I co-authored with Sophia Wedeen, Whitney Airgood-Obrycki, and Christopher Herbert. Indeed, renters living in communities of color, and in high-poverty, lower-income, and lower-rent neighborhoods were more likely to experience distress. This paper also finds that emergency rental assistance (ERA) was similarly concentrated in these neighborhood types, indicating that ERA generally reached the neighborhoods with the greatest need.

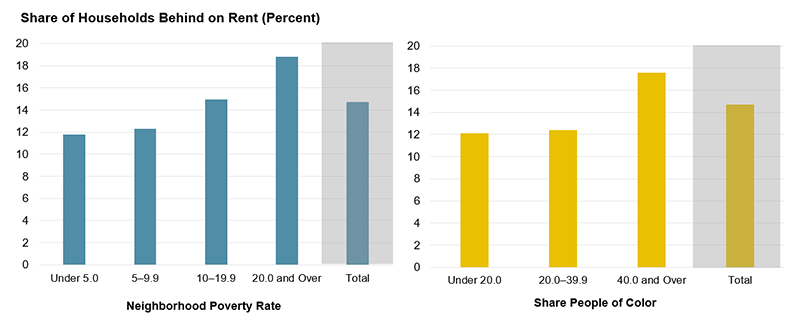

In "The Geography of Renter Financial Distress and Housing Insecurity During the Pandemic,” we use restricted-access data from the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey containing detailed geographic information about where respondents live. We find that 23 percent of renters lost employment income in the month before they were surveyed between April 2021 and February 2022, while 15 percent fell behind on their rent. These rates vary substantially by neighborhood type (Figure 1). For example, fully 19 percent of renters in higher-poverty neighborhoods (where more than 20 percent of the population lives in poverty) fell behind on their rent, compared with 12 percent living in lower-poverty neighborhoods (where under 5 percent of the population lives in poverty). Likewise, financial distress was more common in lower-income and lower-rent neighborhoods, and neighborhoods with higher shares of people of color.

Figure 1: Renters in High-Poverty Neighborhoods and Communities of Color Were More Likely to Fall Behind on Payments

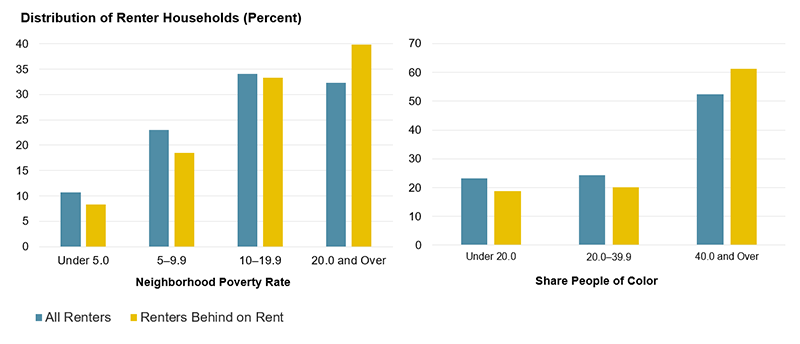

Because renters themselves are concentrated by neighborhood, these differential rates translate into a substantial concentration of financial distress. Indeed, two-fifths of renters behind on their rent lived in higher-poverty neighborhoods while just 8 percent lived in lower-poverty neighborhoods. Meanwhile, enduring patterns of segregation, also a product of longstanding discrimination in housing markets, have contributed to the spatial distribution of employment income losses and rent arrears. Fully 61 percent of households behind on their rent lived in communities of color (where at least 40 percent of the population was people of color) while just one-fifth lived in neighborhoods where the share of people of color was under 20 percent (Figure 2). In the paper, we further examine how neighborhood-level financial distress varies by region as well as by the income and race/ethnicity of the household, finding that rental arrears were especially wide-ranging in the Northeast and that patterns of distress by neighborhood type largely persist regardless of the income of the household.

Figure 2: Rental Arrears Were Concentrated in High-Poverty Neighborhoods and Communities of Color

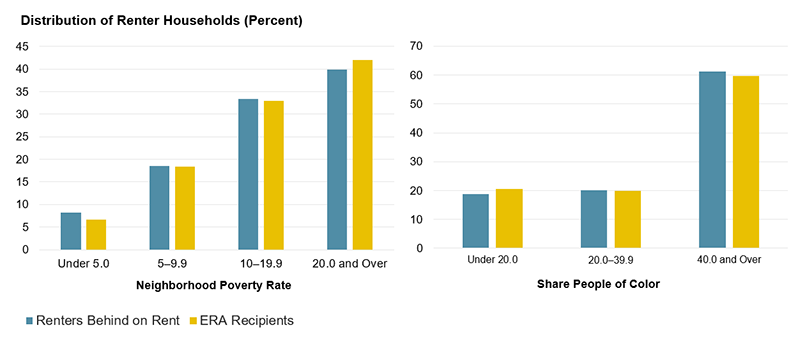

Given this concentration of rental arrears in certain kinds of neighborhoods, we also assess the extent to which ERA reached neighborhoods with the greatest need. We find that the share of renters who applied for and ultimately received rental assistance was similarly concentrated in neighborhoods experiencing the greatest financial difficulties. For example, about two-fifths of ERA recipients lived in higher-poverty neighborhoods, while three-fifths lived in communities of color—comparable to the concentration of renters behind on their rent (Figure 3). While this is true in our findings nationally, it’s worth noting that ERA administration varied considerably by state and that ERA disproportionately targeted states with smaller populations, potentially bypassing qualified renters who were struggling to make their payments in other states.

Figure 3. Emergency Rental Assistance Was Largely Concentrated in Neighborhoods with the Greatest Need

The geographic context and concentration of renter financial distress is important to understand because it has likely shaped rental property ownership and renter instability in specific neighborhoods. Owners of properties where many tenants are behind on rent might defer maintenance and essential payments like mortgages, utilities, and property taxes. If these units are concentrated in higher-poverty neighborhoods or communities of color, that disinvestment might also be concentrated in these neighborhoods. Moreover, financial distress in these neighborhoods has the potential to increase housing instability, which could negatively impact neighborhoods by rupturing social ties and destabilizing properties.

These findings should inform the development of policies and programs meant to alleviate the financial distress renters have faced since the beginning of the pandemic. Indeed, differences in financial distress by neighborhood type should provide some basis for targeting assistance and help with assessments of program efficacy, especially when detailed demographic information on program participants is not collected or is deemed too sensitive. In combination with household characteristics, geography could aid in designing and assessing not only ERA, but also eviction prevention and diversion programs and other forms of assistance for renters and landlords. Such efforts might mitigate the harms of disinvestment and the risk of heightened eviction in neighborhoods experiencing high rates of distress.