Racialized Recovery: Postforeclosure Pathways in Boston’s Neighborhoods

While many studies have shown that most foreclosures during the Great Recession occurred in minority or disadvantaged neighborhoods, few have carefully examined neighborhood-level differences in ownership and management practices of those who bought properties in high-foreclosure locales. However, in a paper recently published in City and Community, Jackelyn Hwang, a former Meyer Doctoral Fellow who is now an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Stanford, shows significant, neighborhood-level variations in ownership patterns and management practices.

In “Racialized Recovery: Postforeclosure Pathways in Boston Neighborhoods,” which is based in large part on research she did as a Meyer Fellow, Hwang found that while corporations were more likely to purchase foreclosed properties in predominantly black neighborhoods, owner‐occupants were more likely to buy units in racially and ethnically mixed neighborhoods where a large share of residents were white. The differences, she found, are important because compared to other owners, corporations were less likely to act in ways that promote neighborhood stability, such as maintaining their properties or holding onto them for long periods of time.

Hwang reached these conclusions after detailed analyses of data on foreclosures, property sales, and a variety of city records from 2006, when foreclosures began to increase in Boston, to 2011, the last year before they declined dramatically. During this time, there were 4,000 foreclosures in the city, where the foreclosure rate (the share of all housing units in foreclosure) peaked at 1.77 percent in 2008, a little less (and earlier) than the peak national rate of 2.23 percent in 2010.

Hwang ultimately identified 1,504 single-family homes and condominiums that went all the way through the foreclosure process (from filing to sale at auction) in Census block groups with above-average foreclosure rates, which comprise one quarter of the city’s block groups. Over 80 percent of Boston’s foreclosures occurred in Dorchester, Roxbury, Mattapan, Hyde Park, and East Boston, which are five of the city’s 15 planning districts but contain only 30 percent of Boston’s housing units. Over 90 percent of the foreclosures in these five planning districts occurred in these high-foreclosure block groups. Compared to the city as a whole, the high-foreclosure block groups were, on average, home to about half as many whites and twice as many blacks. However, high-foreclosure block groups were not the city’s most disadvantaged areas, which have large numbers of publicly subsidized housing units that are not likely to be subject to foreclosure.

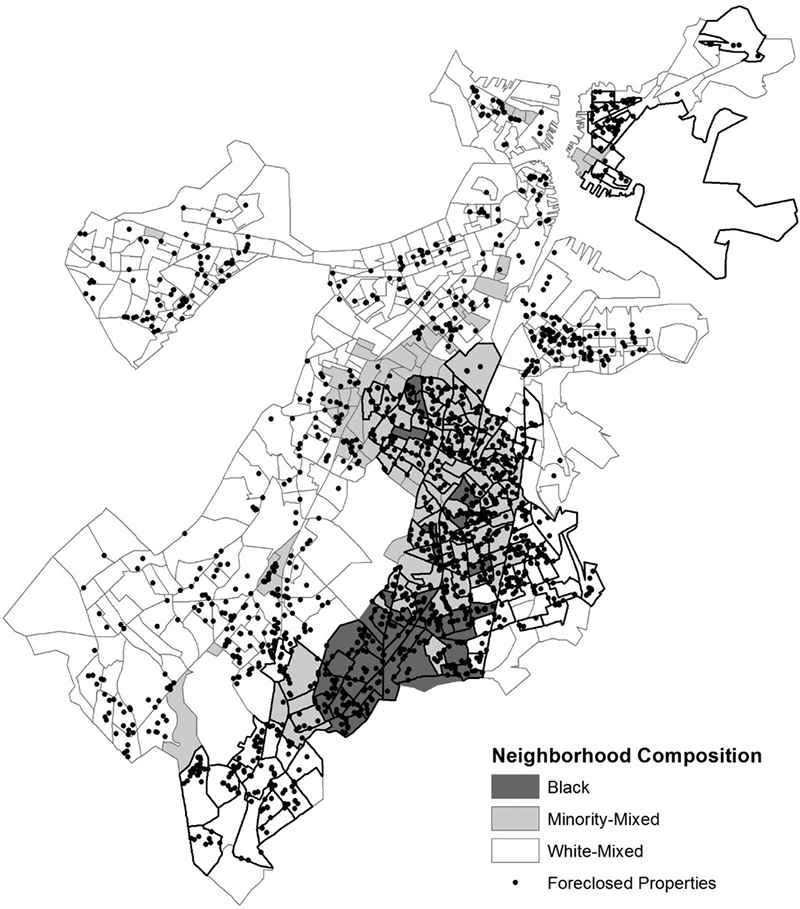

Moreover, the demographics of high-foreclosure block groups varied widely. Hwang calculated that 32 were “predominantly black” (over 50 percent of residents were black and no other racial or ethnic group accounted for more than 10 percent of the residents). Another 46 were “white-mixed” neighborhoods where more than 30 percent of the residents were non-Hispanic whites and no more than 50 percent were from another racial or ethnic group. (Of these, only five were over 80 percent non-Hispanic white.) The remaining 90 block groups were “minority-mixed” neighborhoods (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Foreclosed Properties in Boston by Block Group’s Racial and Ethnic Composition, 2006-2011

Note: “Black” neighborhoods are at least 80 percent non-Hispanic black in 2000; “White-Mixed” neighborhoods are at least 30 percent non-Hispanic white and no more than 50 percent of another race or ethnicity; “Minority-Mixed,” are the remaining tracts.

Source: Author’s calculations from various data sources.

Different types of purchasers tended to concentrate in different types of neighborhoods. While corporations purchased about 40 percent of the foreclosed properties in predominantly black block groups and 43 percent in minority-mixed ones, they bought only 29 percent of those properties in white-mixed areas. In contrast, owner-occupants purchased 40 percent of the foreclosed properties in white-mixed block groups but only 30 percent in predominantly black areas and 20 percent in minority-mixed areas. And individual investors purchased 24 percent of the properties in predominantly black neighborhoods, 29 percent in white-mixed neighborhoods, and 31 percent in minority-mixed areas.

Maintenance practices and investment strategies also varied. By two years after a postforeclosure sale, residents had called the city to complain about conditions in about 9 percent of properties purchased by corporations but only 4.9 percent of those bought by individual investors and 2.4 percent bought by owner-occupants. During the same time frame, 11 percent of the corporate-owned units had inspections violations, compared to 10 percent of those owned by individual investors and 6.8 percent of those bought by owner-occupants. And while 37 percent of properties purchased by corporations were resold within two years, only 29 percent of properties purchased by individual investors were resold in that time. Investors purchased 58 percent of the resold properties that had been purchased by corporations, 44 percent of those that had been bought by individual investors, and 28 percent of those purchased by owner occupants.

These findings are significant because there is extensive research documenting the negative consequences of living in neighborhoods with high residential instability, low homeownership, and high levels of disorder. Given this, the findings “imply that predominantly black neighborhoods hit hard by foreclosures in Boston were left further behind in the recovery from the housing crisis compared to other hard‐hit neighborhoods.” This, in turn, suggests that efforts to stabilize hard‐hit neighborhoods as they recover from the crisis (and future crises, if they occur), “require resources and incentives for both owner‐occupants and investors—both small and large—to maintain their properties and for investors to fill properties with long‐term renters.” Without such interventions, Hwang warns, “neighborhood inequality by race and ethnicity will remain durable through the housing recovery and beyond.”