Overcoming Barriers to Immigrant Homeownership in the US

Immigrants make up a growing share of the US population and by 2040 foreign-born households will constitute the primary source of new housing demand. However, little is known about both the unique barriers and opportunities that immigrants face as they seek to buy a home. Our new working paper, “Immigrants’ Access to Homeownership in the United States: A Review of Barriers, Discrimination, and Opportunities,” helps fill that gap by reviewing existing scholarship on immigrant homeownership.

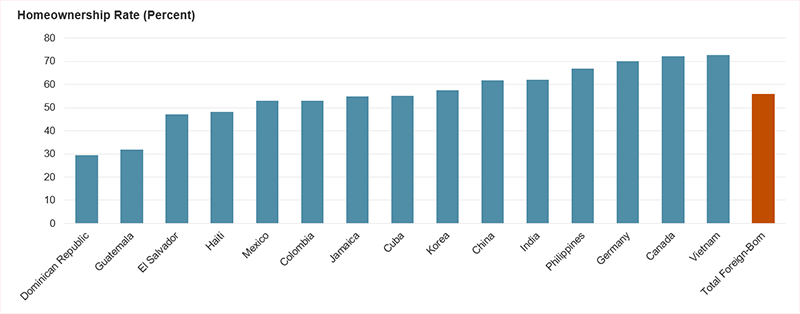

In 2021, over one in seven US households (16 percent) were headed by a foreign-born resident. By far the highest shares of immigrants had moved from Mexico, followed by India, China, the Philippines, and Cuba. Homeownership rates varied sharply between different groups of immigrants (Figure 1). In 2021 the homeownership rates for the ten largest groups of immigrants ranged from a high of 73 percent of households from Vietnam, to a low of 29 percent of households from the Dominican Republic.

Figure 1: Immigrant Homeownership Rates Vary Widely by Country of Origin

Immigrants Face Unique Barriers in Becoming Homeowners

General factors such as age and income influence immigrants’ ability to become homeowners as does the amount of time they have been in the country. Research found that in 2000, only 16 percent of Hispanic immigrant households who lived in the United States for five years or less owned a home, compared to 61 percent of Hispanic immigrant households who had been in the country for 21 years or more. Indeed, duration of residence relates to the capacity to surmount other barriers to homeownership over time, including shifting into a more secure legal status, moving away from lower-opportunity, segregated neighborhoods, gaining better employment, and building savings and credit history in the United States. Immigrants – particularly immigrants of color and those who are undocumented – face unique barriers when trying to buy a home.

Legal status can complicate immigrants’ paths to homeownership as those who are undocumented or have temporary visa status often have less secure and well-paying jobs, find it hard to access the banking system, and lack a sense of security in the United States. While contemporary discussions often focus on undocumented versus “legal” immigrants, immigrants experience many gradations of legal status, including within their own households, that make it harder to become homeowners. For instance, while DACA recipients are eligible to apply for Federal Housing Administration insured mortgages and to receive free homeowner counseling through HUD-approved counseling agencies, the uncertain future of DACA may prevent them from feeling safe enough to put down roots and buy a home.

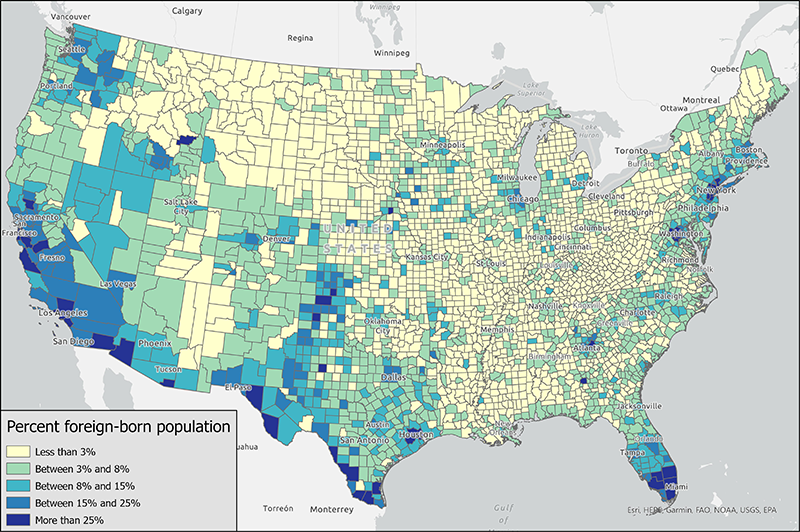

In addition, the locations where immigrants have settled can present distinct challenges, due to local variations in housing costs and available housing stock. Most immigrants first settle in high-cost urban areas such as New York City and Los Angeles but since the 1990s many immigrants have moved to new destinations in rural areas, Sunbelt cities, and suburbs. Figure 2 shows which counties across the United States had some of the highest shares of foreign-born individuals in 2020. While many immigrants still live in traditional immigrant gateways, like the New York and Miami areas, immigrants also make up a larger share of the population in suburban and rural counties across the southwest, including in Texas, New Mexico, and Nevada.

Figure 2: Counties with the Largest Shares of Immigrants Are in the West, Northeast, and Florida

National Origin Housing Discrimination Against Immigrants Remains Understudied

Our paper also highlights the underrecognized issue of housing discrimination based on national origin, alongside birthplace, ethnicity, ancestry, culture, and language. Despite evidence of residential segregation experienced by immigrants, we have very little research to help us understand who experiences national origin discrimination in housing. We do know, however, that during the 1990s and early 2000s Hispanic households were much more likely to be offered subprime mortgage products than white applicants, even when they would have qualified for a prime product. Today, applicants of color, including Asian applicants, face higher risks of mortgage application denial.

Immigrants Rely on Innovative Housing Finance and Co-Ethnic Support

To bypass financing barriers that immigrants may encounter, immigrant homeowners often pool resources with extended families or rely on alternative financing sources, including the use of rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs). ROSCAs are an informal, unbanked savings tool, often formed between groups of colleagues, friends, or family members who already have a foundation of mutual trust. ROSCAs help immigrants reach saving goals quicker, access no-interest loans, and provide an institutional structure of trust and mutual expectations to help save. While more research is needed, previous work found that ROSCAs have helped immigrants save for down payments and for home repairs.

Policy Recommendations

Policies intended to support first-time homebuyers could also address the challenges of immigrants. This includes financing innovations such as counting regular remittance payments as evidence of strong credit histories. Considering the ways that immigrants in particular have relied on extended household formation to afford homeownership, underwriting standards can also be designed to be more inclusive of the financial contributions of non-buyer extended household members. Downpayment and wealth building savings programs can learn from the strengths of informal rotating savings and credit associations, such as community-building, mutual accountability, and the ways these groups cultivate saving as a long-term, habituated practice.

The increasingly diverse pool of homebuyers that immigrants represent could also spur efforts to improve diversity in key aspects of the housing ecosystem that will serve these buyers. This includes lenders, realtors, and appraisers who speak a wider range of languages and personally appreciate the unique challenges that immigrants may face as they seek to buy a home.