Older Adults Living with a Partner Were Better Able to Cope with the Pandemic

Older adults living with partners had more economic resources compared to other households before the pandemic, and once the pandemic began, they experienced fewer disruptions to their finances or personal assistance according to a new paper I co-authored with my colleagues, Jennifer Molinsky and Chris Herbert. In Household Composition, Resource Use, and the Resilience of Older Adults Aging in Community During COVID-19, which was published by the Center for Financial Security at the University of Wisconsin, and supported by the Social Security Administration (SSA), we examined how household composition impacted resiliency for older adults during the pandemic. Using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we compared the pre-pandemic resources of three groups of people aged 50 and older: those who lived alone, with a partner, and with others. We then examined experiences of health, financial security, and access to care during the first months of the pandemic.

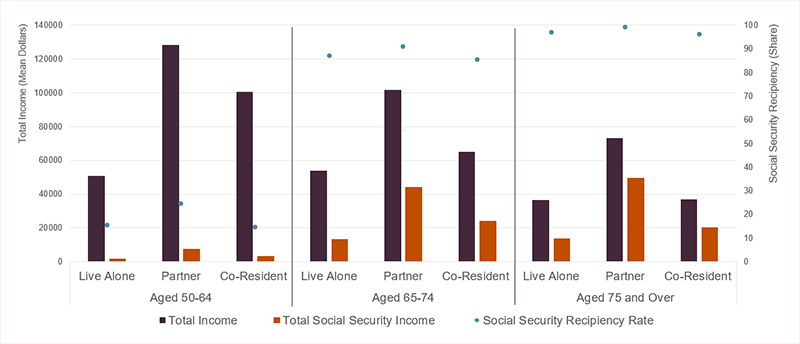

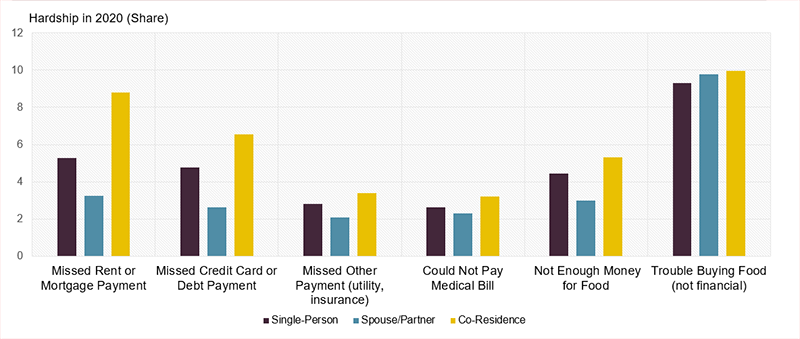

Before the pandemic, adults aged 50 and older who lived with their spouse or partner but no others in the home had fewer functional difficulties (such as with mobility or dressing) than other household types. They had the highest rates of homeownership and highest income among the three composition types. With two recipients in the household, Social Security income comprised a larger share of partner household income, especially at older ages (Figure 1). These households experienced the fewest economic hardships during the pandemic; they were less likely to have trouble paying for food, housing costs, and medical bills. They also experienced the fewest mental health challenges and the lowest rate of COVID-19 infections as of late-summer of 2020.

Figure 1. Older Adults Living with a Partner Had More Income than Older Adults Living Alone or with Others

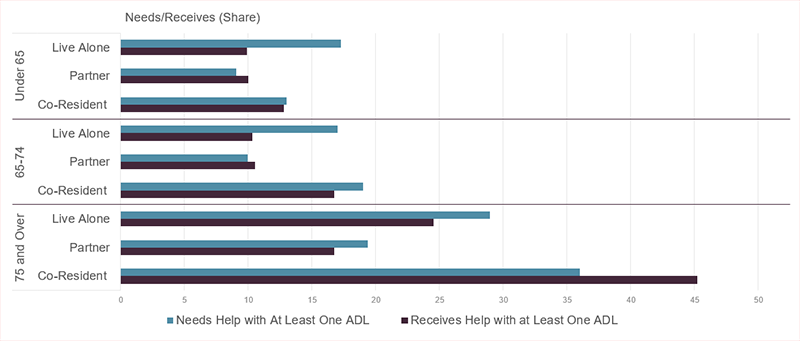

Residents of single-person households had lower incomes and were more likely to rent their homes. With age, people increasingly become widowed, so people living alone were older, with a mean age around 71 years compared to 67 in partner households and 65 for co-residents. Without their spouse or partner, many also lost income, which can be especially challenging for renters who pay the same housing costs no matter who lives in the house and who are more likely to experience housing cost burdens (paying more than 30 percent of income for housing). Advanced age is also linked to greater need for assistance, and people living alone needed as much or more functional support as those living in co-resident households, but they received less on average (Figure 2). Compared to other household types, this assistance was more likely provided by a paid professional. Supports were not equally stable, as during the pandemic, older Black or Hispanic lower and middle-income residents of single-person households experienced a disproportionate drop in total hours of assistance. People living alone were also more likely to report feeling depressed, sad, or lonely, with 32 percent feeling lonely in 2020 as compared to 18 percent of co-residents and 22 percent of partner household residents.

Figure 2. Before the Pandemic, Older Adults Living Alone Received Less Support Relative to Their Need

Co-residents, or older adults who lived with roommates or extended family (with or without a spouse), were less likely to own their homes than residents of partner households and their household income tended to be higher than single-person households, largely due to multiple income streams. After age 75, these residents needed the most assistance with daily living and they received the most support, typically from adult children. This support and assistance remained more stable through the pandemic than for people who lived alone. However, by the end of the summer of 2020, co-resident households had the highest rate of COVID-19 infections. They also experienced the most economic hardship, with almost 10 percent missing a housing payment sometime in the spring or summer of 2020 (Figure 3). Many of these households were multigenerational and dependent on the employment income of working-aged residents. Twenty-two percent of co-resident households reported that they lost income early in the pandemic.

Figure 3. Older Adults Living in Co-Resident Households Experienced More Pandemic-Related Difficulty Making Housing Payments

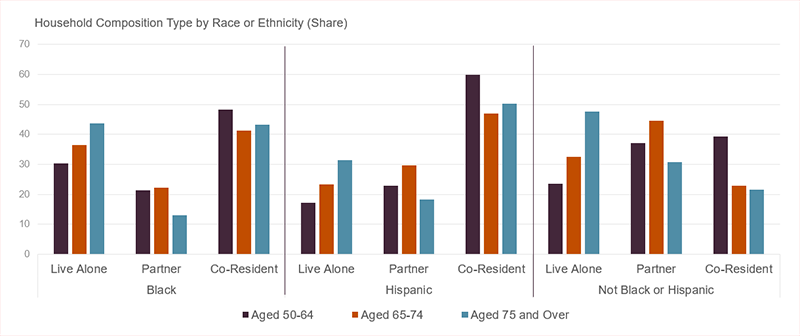

While economic hardships and unmet needs for support were concentrated in single-person and co-resident households both before and during the pandemic, partner households were least likely to include a Black or Hispanic resident. This raises equity concerns about the demographic distribution of households who are most vulnerable to a shock and households who experience more security and stability (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Co-Residence Is Particularly Prevalent among Black and Hispanic Older Adults

With the population of adults aged 75 and older expected to increase by 48 percent between 2020 and 2030, the number living in co-residence or alone will increase. There are opportunities to increase the security of these households and improve their resilience to disruption. Paid family caregiving could help stabilize income and cost burdens could be reduced for residents in publicly subsidized housing by increasing flexibility to accommodate household composition changes. People living alone who depend on professional assistance will be less vulnerable to disruption if public programs that provide professional care are expanded to support more low and middle-income older adults. Policymakers should also reconsider social security benefit formulas that reduce income and threaten financial stability when a spouse dies. A more robust safety net could ensure that residents aging in all types of households have access to the resources they need to navigate disruptions.