Lower-Income Renters Have Less Residual Income than Ever Before

Renter household incomes fell in the first two years of the pandemic as rents increased, leaving many renters with little money to spend on all their other needs. In fact, our analysis of American Community Survey data found that, in 2021, the median renter household making less than $30,000 a year had just $380 left over each month after paying rent. This is not only 22 percent less than what they had at the beginning of the pandemic but it’s the lowest amount they have had on hand in more than 20 years.

According to our analysis, the median monthly household income decreased 2 percent (down $85) from 2019–2021 while the median rent rose 3 percent ($37) in real terms. As a result, the median residual income—the amount of income left over after paying rent and utilities each month—dropped by 5 percent leaving renter households with $130 less each month.

Despite the overall economic recovery, renter incomes were hit harder by pandemic job losses. Additionally, some roommate households with multiple wage earners may have taken advantage of higher apartment vacancy rates early in the pandemic and formed separate, single-earner households. This resulted in a decline of about 279,000 renter households making at least $75,000 from 2019–2021. At the same time, there was a net gain of 223,000 households with incomes under $30,000 and just over 102,000 households with incomes in the $30,000–74,999 range. These shifts led to a $1,000 drop in the median renter household income to $43,500.

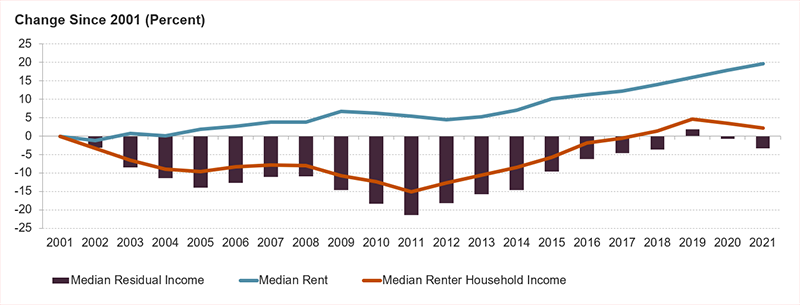

While renters’ incomes fell, rents kept rising, reversing recent affordability gains (Figure 1). From 2001–2011, median rents grew 5 percent in real terms as increasing renter demand hit markets leading up to and in the wake of the Great Recession. Renter incomes took a substantial hit from 2008–2011 during the height of the economic crisis, leaving median incomes 15 percent below their 2001 level. In the most recent decade, renter household incomes started catching up with rent growth but these modest gains in overall affordability were not enough to close the gap between rents and incomes.

Figure 1: Income and Rent Trends During the Pandemic Reversed Modest Affordability Gains in Recent Years

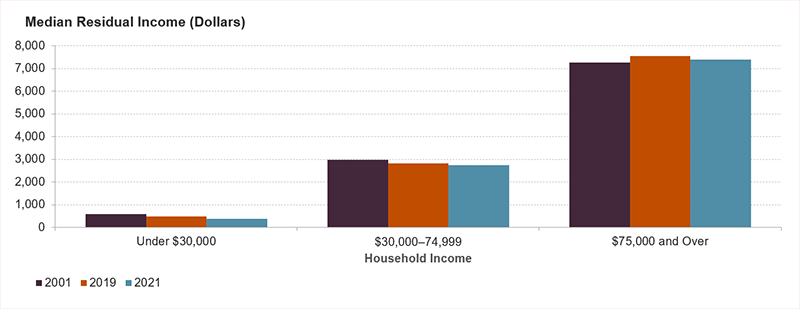

Falling incomes and rising rents during the pandemic eroded affordability once again, leaving renter households with less residual income. In 2021, the median renter had a monthly residual income of about $2,450. This marked a $130 decrease since the beginning of the pandemic and was also lower than the median residual income in 2001 ($2,530) when adjusted for inflation. Lower-income renters have been hit especially hard by pandemic job losses amid rising rents. In 2021, renter households with incomes under $30,000 had just $380 left each month after paying rent and utilities (Figure 2). This was a decrease of more than $100 since the beginning of the pandemic and was $200 less than 2001 levels. Middle-income renters earning between $30,000 and $75,000 had substantially more residual income at $2,750 but dropped $80 since the beginning of the pandemic, and was down $220 since 2001. Even higher-income households, whose residual incomes have increased over the long term, saw their residual incomes drop during the pandemic. However, these households are more able to absorb rising rents.

Figure 2: Lower-Income Renters Have Less Income Left Over After Paying Rent Than Ever Before

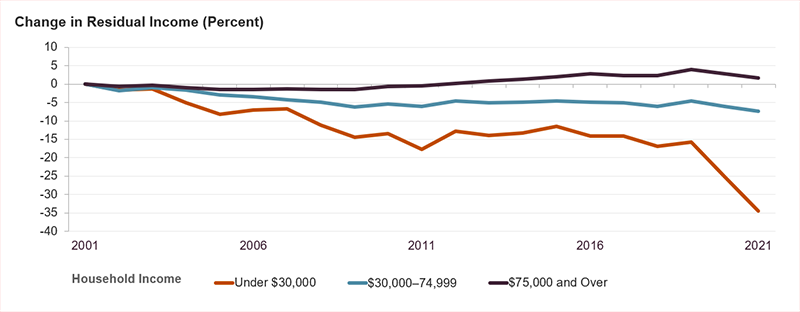

The latest trends highlight the widening inequality among renters. Indeed, residual incomes for the lowest-income renter households have decreased 35 percent since 2001 as their incomes dropped and rents rose (Figure 3). Higher-income households have benefited from rising incomes that outpaced rent growth, resulting in a 2 percent increase in residual incomes over the same period.

Figure 3: Inequality Is Increasing Among Renters as Affordability for Lower-Income Households Worsens

Declines in residual incomes have significant implications for household well-being. Even before the pandemic, nearly two-thirds of working-age renters did not have enough to cover a basic standard of living after paying their rent each month. And as we’ve noted in previous reports, lower-income households spending more than half of their incomes on rent spend less on vital healthcare and food expenses than their unburdened counterparts. Over the last year, inflation has only added pressure to already strapped household budgets—a topic we’ll discuss in a forthcoming blog—putting even more stress on renter households.