The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Landlords in Albany and Rochester, New York

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recession have made it harder than ever for low- and moderate-income US households to pay their rent, fueling a crisis in which an estimated $25-34 billion in rental payments is currently outstanding.

The impact of rental non-payment on small mom and pop landlords, who are most likely to house lower-income renters, and who are more likely to be socially and economically vulnerable themselves, has been significant. To shed further light on this issue, in June and October 2020, I surveyed owners with three or fewer rental properties in Albany and Rochester, New York. For each property in their portfolio, I asked these mom and pop landlords how COVID-19 has impacted their business, and how they are managing and responding to the pandemic.

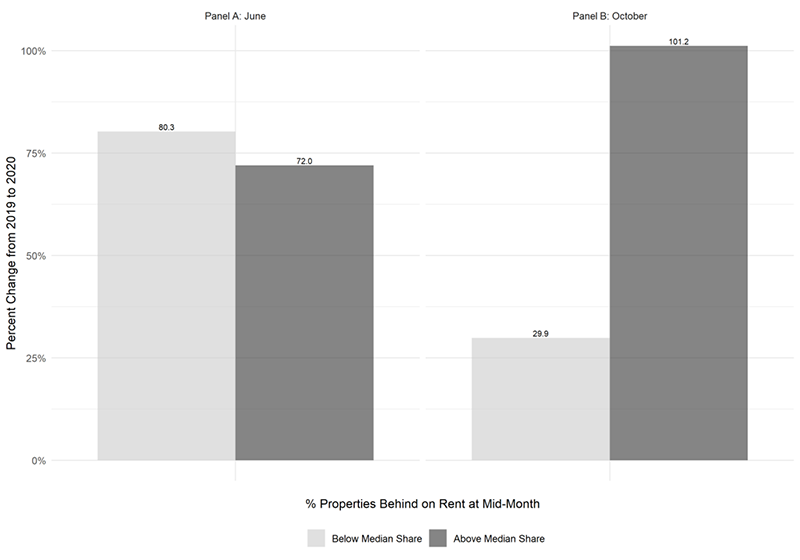

Overall, I find that small landlords’ tenants were significantly more likely to be behind on June and October rent in 2020 relative to 2019. I also find that the evolution of rental payment over the course of the pandemic has varied according to neighborhood social and demographic characteristics. For example, Figure 1 shows year-over-year changes in the percent of properties in arrears at mid-month for June and October, for neighborhoods with a below-median and above-median share of residents of color. In June, there was a dramatic increase in the proportion of small landlords’ rental properties behind on rent in both types of neighborhoods. In fact, at around 80 percent, the year-over-year increase in mid-month arrearage was larger in neighborhoods with more non-Hispanic white residents, due in part to their higher baseline rental payment rates.

Figure 1: Year-over-Year Changes in 15th of the Month Rental Payment, by Neighborhood Share of Residents of Color

Notes: This figure plots year-over-year changes in June and October rental payment rates for all rental properties owned by small landlords in Albany and Rochester, NY, by neighborhood share of residents of color. In June 2019, 17% of properties in below-median neighborhoods were behind on rent at mid-month, compared to 29% in above-median ones. In October 2019, 26% of properties in below-median neighborhoods were behind on rent at mid-month, compared to 28% in above-median ones.

By October, the mid-month rental payment rate improved substantially in neighborhoods with a higher share of non-Hispanic white residents, though arrears were still up from the prior year. In neighborhoods with a higher share of residents of color, on the other hand, the proportion of rental properties behind on rent at mid-month more than doubled from 2019 to 2020 and increased by 30 percentage points from June. The continual decline of rental payment rates in these neighborhoods likely reflects the fact that Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to work in fields such as the service sector where unemployment is still high, and provides evidence of another domain—housing—in which low-income Americans and people of color have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

Small landlords’ most common property-level responses to rental non-payment have been to defer maintenance (20 percent) and put tenants on rental payment plans (30 percent). For about 5 to 10 percent of the properties I studied, small landlords took other steps including delaying property tax payments, imposing late fees, and evicting tenants. In addition, some raised rents, while others lowered them.

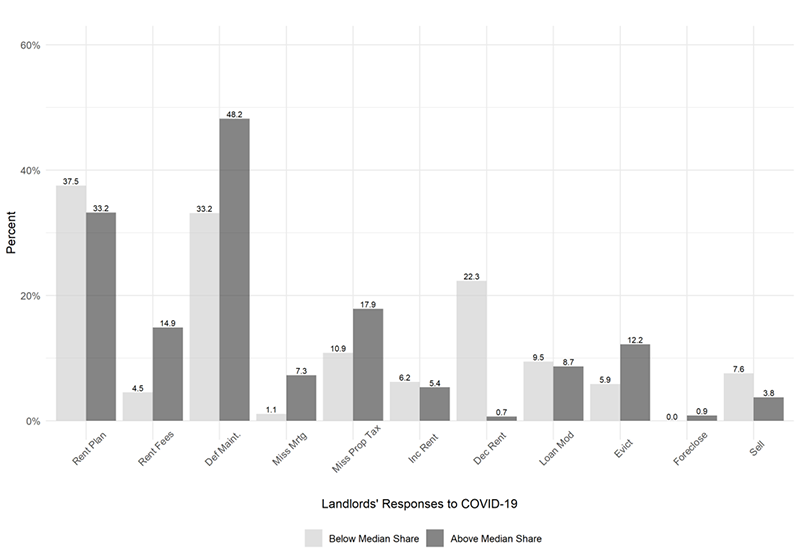

I also found that, even holding rental payment rates constant, small landlords were more likely to defer maintenance and evict tenants in low-value properties and neighborhoods with a higher share of residents of color. Figure 2 shows landlords’ responses to the pandemic for properties behind on October rent at mid-month, separated by neighborhood racial and ethnic composition.

Figure 2. Landlords’ Responses to COVID-19 at Properties Behind on October Rent, by Neighborhood Share of Residents of Color

Notes: This figure plots the property-level responses to COVID-19 of small landlords in Albany and Rochester, NY, by neighborhood share of residents of color, among properties behind on October rent as of mid-month. The property-level responses occurred at some point between March and October 2020. Responses do not sum to 100 because landlords could choose multiple responses.

Among this sample, nearly half of properties in neighborhoods with more residents of color had deferred maintenance sometime between March and October, compared to about one-third in communities with more non-Hispanic white residents. Additionally, properties in neighborhoods with a higher share of residents of color were more than twice as likely to have tenants facing eviction. And perhaps most strikingly, less than 1 percent of properties in these neighborhoods had rents lowered from March to October, compared to 22 percent otherwise.

This research highlights both the financial stress mom and pop landlords are currently facing and how their responses to this stress, most notably through evictions, may serve to reinforce existing housing struggles for vulnerable tenants. Ultimately, this creates a cycle that increases financial and housing instability among both economically at-risk property owners and renters. In the absence of widespread rental assistance programs for landlords and tenants alike, there is little reason to believe this vicious cycle will end.