Although the Population is Rapidly Aging, Young Adults Will Still Drive the Demand for New Housing

Hardly a day goes by when we are not reminded about how rapidly our population will age over the next several decades as the baby boom crosses the 65+ threshold. For housing analysts, an aging population is often thought of as the key demographic trend that will drive housing consumption over the next 20 years. This shift in age structure does not, however, mean that elderly population growth will be the primary driver of the demand for newly built housing. While most of the population growth will take place among the elderly, that increase, for the most part, does not represent people active in the housing market. Younger age groups will not experience much population growth, but this is because, among those under 35, large cohorts are replacing other large cohorts – sometimes a bit smaller and sometimes a bit bigger. But most of the members of these large younger cohorts will enter the housing market for the first time in their 20s and 30s. They will consume most of the newly built housing. Here are the details.

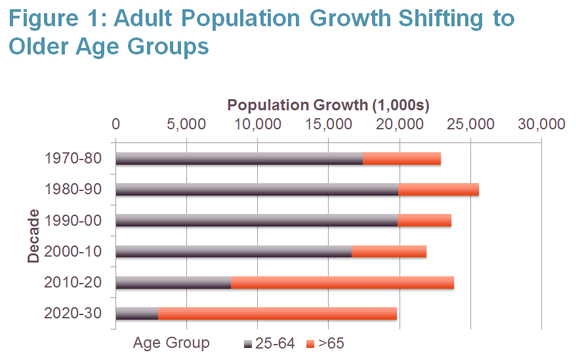

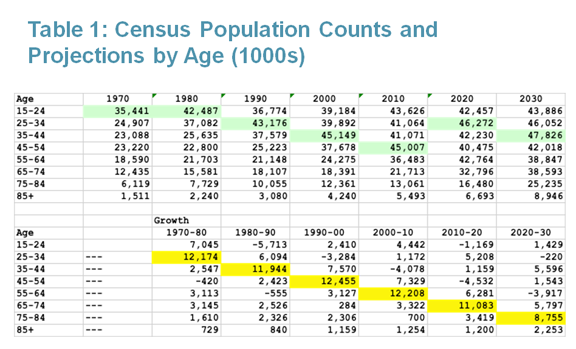

The aging of the United States population is dramatically shown in Figure 1. Between 1970 and 2010, most adult population growth took place in the under 65 age groups. Starting in 2010, aging baby boomers begin to shift most of the population growth to the over 65 age groups. Each decade during the past 40 years (the leading edge of the baby boom, those born 1946-1955) has provided the biggest share of population growth of any 10-year age group (lower panel of Table 1 cells highlighted in yellow). In the 1970s, baby boomers created growth among young adults, gradually shifting the growth to older and older age groups in successive decades. The dominance of baby boomers in the population growth equation will persist until sometime after 2030 when they begin to reach the end of their lives in large numbers.

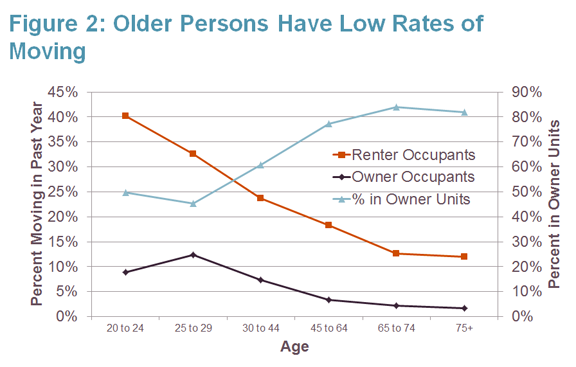

Many are quick to conclude that, since population growth drives most of the demand for new housing construction, we must primarily build for the elderly. The problem with this logic is that elderly population growth does not represent new additions to the population, and most elderly are already housed quite comfortably and show little inclination to move to a different residence. Strong elderly population growth is simply the aging of a large cohort replacing the smaller cohort that came before them – they are not new people entering the housing market. As I’ve discussed in a previous post, for the remainder of this decade and the next, elderly baby boomers will largely age in place. Fewer than 4 percent of the population over the age of 65 changed residence in 2012-13. Over 80 percent of the elderly live in owner-occupied housing. For those 65+ living in owner-occupied housing, the annual mobility rate is now about 2 percent.

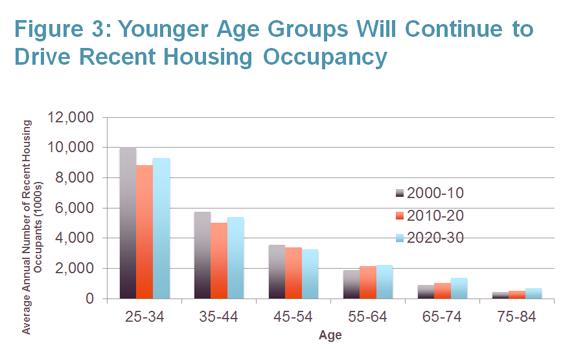

As I mentioned earlier, movers can be thought of as driving the demand for new housing since non-movers by definition stay in their current homes. While the number of people over age 65 is growing rapidly, given the very low mobility rates of this population the number of movers that are elderly will still be small. Multiplying the average size of each 10-year age group of adults (upper panel of Table 1) by the average percentage who change residence each year will give the annual number or persons in each age group that are expected to move over the decade. In the 2000-2010 decade, these movers, or recent occupants, were clearly dominated by young adults age 25-34 (Figure 3). This cohort does not have the largest population; it is about 5 million less in number compared to the baby boomers age 45-54 in 2010 (upper panel of Table 1). But at over 40 million, its size is substantial. Having the highest rate of geographic mobility, 25-34 year olds accounted for almost three times as many recent occupants during the 2000-2010 decade as the largest baby boom cohort. Each year during that decade, persons over the age of 65 averaged only 6.2 percent of total moves (8.5 percent in 2013). Such low representation of the elderly among movers will persist for the foreseeable future. That share is projected to increase only slightly during the next two decades to an average of about 10 percent in 2020-2030 in spite of the large projected growth in the 65+ population. Note that these projections likely bias upward the estimates of demand for new market housing by the elderly because the resident population used as a base in the projections include the elderly living in nursing homes and prisons.

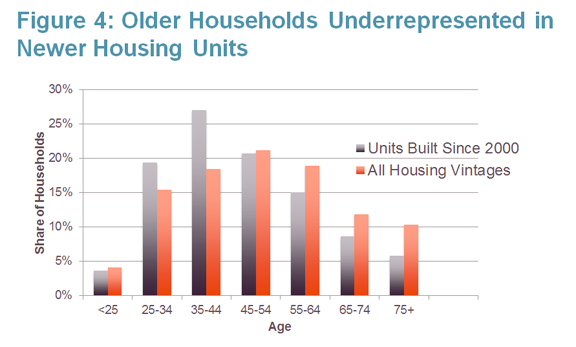

In keeping with their lower mobility rates, older adults are underrepresented in newly built housing. Households over the age of 65 in 2011 accounted for 22.1 percent of all households, but just 14.4 percent of occupants of units built since 2000 (Figure 4). Among all owner heads of households, 26.9 percent were over the age of 65, but just 14.7 percent were heads in owner units built since 2000. However, older households do account for a larger share of heads of households living in new rental units: 13.4 percent of renter heads are elderly, nearly equal to their 13.6 percent share of occupied rental units built since 2000. This greater parity in representation of the elderly in newer rental units is consistent with the higher mobility rates of older renters compared to older owners.

As the large baby boom cohorts age into the 65+ age groups, will they increase the share of elderly who live in newer housing? An increase proportional to their growing share of the adult population (adjusted for their lower mobility rates) is certainly expected. For example, according to recent Joint Center household projections, the elderly accounted for 23.3 percent of all households in 2014, increasing to 26.4 percent in 2020 and to 31.5 percent in 2030 when all baby boomers are over the age of 65. If the elderly maintain their share of households living in newer units at current levels, about 20 percent of newly built units in 2030 will be occupied by heads over the age of 65. But to increase the share of newly built housing occupied by the elderly significantly above that figure, tomorrow’s elderly will need to relocate out of older housing at higher rates than we now observe.

For the next 15+ years, helping the elderly achieve a better fit with their housing will largely involve initiatives to support aging in place. The need for assisted living facilities and nursing homes will gradually increase as the baby boom ages, but the greatest increases will take place after 2030. Whether the elderly are likely to increase their mobility rates within market housing in the near-term future is worth considering. Public and private efforts to provide housing that better serves the needs of an aging population could spur greater mobility among those ages 65+. However, there are a host of demographic, social and economic characteristics of baby boomers that argue for less, not more, geographic mobility among the next generation of elderly. This topic will be the subject of a future blog post.